Printer-friendly PDF file

Printer-friendly PDF fileWestside Observer Newspaper

February 2019 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Severe Shortage of Elderly & Disabled Healthcare Facilities

Supervisor Yee Must Prioritize Full Spectrum

Printer-friendly PDF file

Printer-friendly PDF file

Westside Observer

Newspaper

February 2019 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Severe Shortage of Elderly & Disabled Healthcare Facilities

Supervisor Yee Must Prioritize Full Spectrum

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

Congratulations are in order to D-7 Supervisor Norman Yee for being elected president of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors!

Now, Yee needs to pivot quickly to working collaboratively with Supervisors Hillary Ronen and Ahsha Safai, the San Francisco Public Health Department, and other City leaders to address comprehensive solutions to the full spectrum of facilities that have severe shortages of in-county capacity to serve disabled and elderly San Franciscans, many of whom have been discharged out-of-county. Yee has made scant progress over the past year to address multiple problems that have severely worsened during well over several decades.

Turf Fight Erupts

In its December 2017 issue, the Westside Observer newspaper published an article “Temporary Reprieve From Exile,” reporting that a tug-of-war had erupted between members of the Board of Supervisors over the severe shortage of skilled nursing facilities (SNF) throughout San Francisco, resulting in part from CPMC’s ongoing elimination of SNF beds from its San Francisco hospital chain, and its decision to close San Francisco’s single sub-acute unit at St. Luke’s Hospital.

In its December 2017 issue, the Westside Observer newspaper published an article “Temporary Reprieve From Exile,” reporting that a tug-of-war had erupted between members of the Board of Supervisors over the severe shortage of skilled nursing facilities (SNF) throughout San Francisco, resulting in part from CPMC’s ongoing elimination of SNF beds from its San Francisco hospital chain, and its decision to close San Francisco’s single sub-acute unit at St. Luke’s Hospital.

The SNF shortage contributes significantly to dumping San Franciscans out-of-county, as Yee surely must know.

The tug-of-war involved, on the one hand, Supervisors Safai and Ronen who wanted to focus on the acute shortage of hospital-based and private-sector “freestanding” SNF and sub-acute facilities. On the other hand, Supervisor Yee wanted to focus primarily only on Residential Care Facilities for the Elderly (RCFE’s) and assisted living facilities.

Safai held a first hearing before the Supervisors’ Public Safety and Neighborhood Services (PSNS) Committee on CMPC’s proposed closure of St. Luke’s SNF and sub-acute units on July 26, 2017 that was continued to the “Call of the Chair” of the PSNS Committee. On September 12 the matter was called from the PSNS Committee for a hearing before the full Board of Supervisors sitting as a “Committee of the Whole.”

Safai held a first hearing before the Supervisors’ Public Safety and Neighborhood Services (PSNS) Committee on CMPC’s proposed closure of St. Luke’s SNF and sub-acute units on July 26, 2017 that was continued to the “Call of the Chair” of the PSNS Committee. On September 12 the matter was called from the PSNS Committee for a hearing before the full Board of Supervisors sitting as a “Committee of the Whole.”

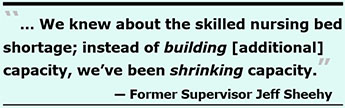

During the September 12 hearing Safai noted the lack of SNF and sub-acute care beds had been a “crisis in the making over the past decade … as we’ve seen a major, major decrease in the number of skilled nursing beds over the last ten to 15 years.” For his part, then-Supervisor Jeff Sheehy noted that during the rebuild of Laguna Honda Hospital [during 2007 to 2010] “we knew then that [the City] was projecting a shortage [of] skilled nursing beds, and the reality is that instead of building [additional] capacity, we’ve been shrinking capacity.”

Supervisors Safai and Ronen were concerned about the City’s crisis of skilled nursing beds shortage, and post-acute and sub-acute care, wanting to explore “in-county, in-hospital solutions for San Francisco.”

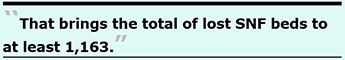

Safai and Sheehy were referring to the “Framing San Francisco’s Post-Acute Care Challenge” report presented to the Health Commission in February 2016 that documented San Francisco had a 43.3% decline in the number of hospital-based SNF beds between 2001 and 2015 alone, from 2,331 beds, to just 1,319 — a loss of 1,012 SNF beds across those 14 years. Tack on the loss of another 151 beds in “freestanding” (i.e., non-hospital-based) SNF beds, from 1,374 to 1,223 in the 12 years between 2002 and 2014, an additional 9% decline in SNF-bed capacity. That brings the total of lost SNF beds to at least 1,163.

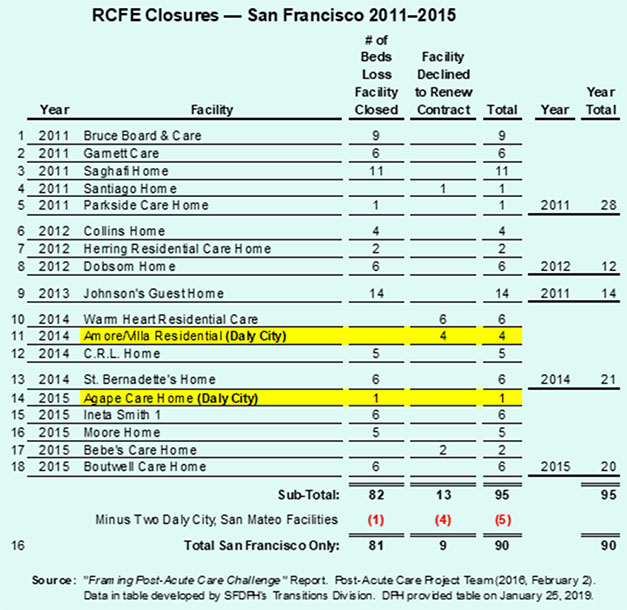

The “Post-Acute Care Challenge” report also documented on numbered page 34 the loss of 16 “board and care” care facilities and 80 RCFE beds that had closed in the five years between 2011 and 2016. That data may have been an anecdotal report. (Note: On December 18, 2018 Yee reported that “San Francisco has been losing assisted living facilities over the last few decades” and “during the last six years, [San Francisco] has lost 20% of our board-and-care beds.”)

Unfortunately, neither the 2016 “Post-Acute Care Challenge” report nor Yee’s most recent December 2018 proposal stratified in raw numbers just how many “beds” have been lost in both RCFE and board-and-care facilities. [The California Department of Public Health responded on February reporting the raw number of licensed RCFE and B&C beds closed and the number of licensed facilities lost per State records; see below for additional data.]

Unfortunately, neither the 2016 “Post-Acute Care Challenge” report nor Yee’s most recent December 2018 proposal stratified in raw numbers just how many “beds” have been lost in both RCFE and board-and-care facilities. [The California Department of Public Health responded on February reporting the raw number of licensed RCFE and B&C beds closed and the number of licensed facilities lost per State records; see below for additional data.]

Prelminary Data on Lost RCFE Beds

The Department of Public Health provided summary data of known RCFE closures between 2011 and 2015 that had been included in the February 2, 2016 “Framing the Post-Acute Care Challenge.” Report. The Post-Acute Care Challenge report wrongly reported San Francisco had lost 80 RCFE beds “in the past five years.” In fact, data provided by the Department of Public Health on January 25, 2019 shows that 90 RCFE beds — not 80 — were lost in that period involving the 16 RCFE facilities, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: “Anecdotal” Data on RCFE Beds Lost in San Francisco

It’s not known “anecdotally” how many additional RCFE facilities and an additional number of beds have been lost in the three years between 2016 and 2018, perhaps due to anyone at DPH failing to ask for that follow-up information.

Interestingly, although San Francisco reported these 16 facilities as being RCFE facilities that have closed in the City, only two of the 16 appeared on a roster of RCFE “facility names” by the State of California dating back to 1975. It’s not known whether California’s licensing division’s data is that seriously out-of-whack, whether those facilities were licensees operating under a different “doing-business-as” facility name, or whether these 16 facilities had operated without ever having obtained State licenses.

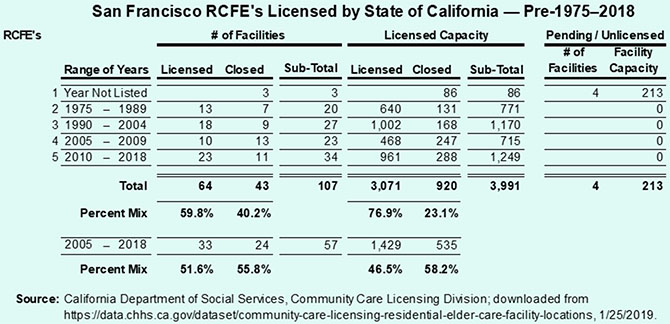

Data provided by California’s Department of Social Services shows a far more serious loss of licensed RCFE facilities and bed capacity across the years.

Table 2: Official California Department of Social Services Data on Licensed RCFE Facilities in San Francisco

Table 2 illustrates, in part, that:

Of those 107 facilities, 43 (40.2%) have closed, per State records, eliminating 920 (23.1%) of the City’s RCFE beds.

Of those 107 facilities, 43 (40.2%) have closed, per State records, eliminating 920 (23.1%) of the City’s RCFE beds. It’s worth repeating that of the 16 RCFE’s that have closed noted in Table 1, only two of them were listed on the list of RCFE’s licensed by the State of California and involved just two beds closed. The portends that of the 90 beds closed in San Francisco shown anecdotally in Table 1, 88 of those 90 beds that may have closed are not in State records, which may push the closed licensed RCFE beds shown in Table 2 from 920 to 1,008.

It’s worth repeating that of the 16 RCFE’s that have closed noted in Table 1, only two of them were listed on the list of RCFE’s licensed by the State of California and involved just two beds closed. The portends that of the 90 beds closed in San Francisco shown anecdotally in Table 1, 88 of those 90 beds that may have closed are not in State records, which may push the closed licensed RCFE beds shown in Table 2 from 920 to 1,008.It should be noted that San Francisco’s Long-Term Care Ombudsman, Benson Nadell, has been highly critical of State record keeping. Nadell noted on January 2, 2018 that the State’s RCFE data rely on licensed facilities, many or which may have already closed but haven’t formally surrendered their licenses, so official data from the State may be inflated by the State’s Community Care Licensing Division that isn’t diligent tracking facility closures before surrender of licenses.

One example of holding on to licenses is that San Francisco held onto its Adult Day Health Care outpatient license at LHH for at least four years before it finally surrendered the license in 2013.

Without knowing the true raw number of lost RCFE beds, it’s difficult to know just how many beds have been lost in addition to the at least 1,163 lost SNF beds.

As the Westside Observer reported in December 2017 San Francisco has discharged — dumped — a significant number of San Franciscans out-of-county due to the shortage of SNF and RCFE beds in-county. Between July 1, 2006 and November 20, 2018 at least 1,479 San Franciscans have been discharged out-of-county, but that only includes 12 years of data for discharges from LHH (FY 06–07 to FY 17–18), nine years of data for SFGH out-of-county discharges (FY 09–10 to FY 17–18), and essentially three years of data for just two of the six private-sector hospitals in the City — CPMC and UCSF (FY 15–16 to FY 17–18). That number is probably far higher due to failure to report all out-of-county discharges.

Chinese Hospital, St. Mary’s, St. Francis, and Kaiser each failed to provide the Department of Public Health the number of San Franciscans they have discharged out-of-county. So, the 1,479 out-of-county discharges dating back to 2006 hasn’t been completely reported and isn’t fully known. The lost 1,163 SNF beds and yet unknown number of lost RCFE and board-and-care beds clearly contributed to the out-of-county discharge crisis. The lost capacity in various types of facilities in the City obviously exacerbated the number of San Franciscans disenfranchised, dumped out-of-county.

Chinese Hospital, St. Mary’s, St. Francis, and Kaiser each failed to provide the Department of Public Health the number of San Franciscans they have discharged out-of-county. So, the 1,479 out-of-county discharges dating back to 2006 hasn’t been completely reported and isn’t fully known. The lost 1,163 SNF beds and yet unknown number of lost RCFE and board-and-care beds clearly contributed to the out-of-county discharge crisis. The lost capacity in various types of facilities in the City obviously exacerbated the number of San Franciscans disenfranchised, dumped out-of-county.

Yee Threw a Wrench into the Hearing

During the September 12, 2017 Committee of the Whole hearing, Yee threw a wrench into the proceedings claiming he asked “for a hearing on these issues” last June, ostensibly referring to SNF and sub-acute level of care facilities. He had not.

In June 2017 Yee had actually called for a hearing to “understand the efforts of City departments regarding institutional housing, particularly assisted living, residential care facilities, and small beds for seniors in San Francisco.” Those are separate, important problems from the issues of sub-acute and SNF level of care, which Yee should know aren’t synonymous although are obviously interrelated.

Yee’s Anemic Efforts

As the Westside Observer reported in March 2018 (“Financing 250 Laguna Honda Senior Housing”), Yee had been approached at some point to support a 50-unit senior housing project at 250 Laguna Honda Boulevard proposed by Christian Church Homes on the Forest Hill Christian Church site. Before anyone knew it, and surprising even Yee, the developers expanded it to a 150-unit project, eliminating the chapel.

The project eventually went down in flames, in part due to a messy lawsuit — El Bethel Arms vs. Christian Homes Church — involving potential fraud against El Bethel. When El Bethel prevailed in court, Yee was dismayed. Eventually the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD) yanked its planned funding for the project, not due to neighborhood opposition but rather due to the seismic stabilization of the hillside behind 250 Laguna Honda Boulevard that proved cost-prohibitive. MOHCD would have had to reduce the 150 units to 75 units which made it financially infeasible and unviable. At that point, MOHCD yanked the project’s financing and it was scrapped.

Yee’s First Proposal to Build on LHH’s Campus (DOA)

Yee’s First Proposal to Build on LHH’s Campus (DOA)

The Westside Observer reported in July 2018 (“Monetizing Laguna Honda Hospital Campus”) that in March 2018 Yee’s then-legislative aide, Nick Pagoulatos, began pitching a proposal in March 2018 to the Department of Public Health (DPH) and the Mayor’s Office of Housing (MOHCD) to build a six-story building with up to 160 units of housing for seniors on LHH’s campus, with a spectrum of options for those who need assisted living, skilled nursing, and independent living (presumably including market-rate units).

Pagoulatos appears to have then authored and submitted a draft document on May 15, 2018 to MOHCD’s director Kate Hartley and Amy Chan, and to DPH titled “LHH Ting Project Description” outlining a proposal to Assemblyman Phil Ting seeking funding for a feasibility study. Hartley and Chang deleted both the 160-unit description, and flatly ruled out building either assisted living or RCFE units on LHH’s campus, saying LHH’s site “wasn’t big enough” and was too small.

Pagoulatos appears to have then authored and submitted a draft document on May 15, 2018 to MOHCD’s director Kate Hartley and Amy Chan, and to DPH titled “LHH Ting Project Description” outlining a proposal to Assemblyman Phil Ting seeking funding for a feasibility study. Hartley and Chang deleted both the 160-unit description, and flatly ruled out building either assisted living or RCFE units on LHH’s campus, saying LHH’s site “wasn’t big enough” and was too small.

Pagoulatos’ initial proposal — heavily edited by Chan and Hartley — was submitted to Ting, but Ting’s Office refused to disclose what precisely was being asked of him. The Assembly’s Committee on Rules claimed on June 22, 2017 that California’s Legislative Open Records Act (LORA) exempts from disclosure “correspondence to individual Members of the Legislature and their staffs.” Because my records request didn’t identify any existing legislation, the Committee on Rules declined to respond.

Yee’s first May 2018 proposal to build on LHH’s campus was essentially dead on arrival.

Yee’s Second Proposal to Build a Significantly Larger Project on LHH’s Campus

Undeterred, Yee tried again proposing to build a significantly larger project on LHH’s campus, despite having previously been shot down by MOHCD. In a draft position paper dated December 18, 2018 on his letterhead Yee pitched constructing a “Life Care Facility” (similar to Continuing Care Retirement Communities) to San Francisco’s new Dignity Fund proposing a spectrum of facilities on LHH’s campus, including 1) An unstated number of independent senior housing units (perhaps including market-rate units); 2) An unstated number of assisted living units; 3) a 30-bed RCFE, several of which beds would be “kept open” for patients discharged from LHH; 4) Ideally, an unstated number of Adult Day Health Care (ADHC) slots for people needing day-care supervision; and 5) Ideally, preschool to foster “intergenerational connections” between the elderly and two- to three-year-old preschoolers.

Undeterred, Yee tried again proposing to build a significantly larger project on LHH’s campus, despite having previously been shot down by MOHCD. In a draft position paper dated December 18, 2018 on his letterhead Yee pitched constructing a “Life Care Facility” (similar to Continuing Care Retirement Communities) to San Francisco’s new Dignity Fund proposing a spectrum of facilities on LHH’s campus, including 1) An unstated number of independent senior housing units (perhaps including market-rate units); 2) An unstated number of assisted living units; 3) a 30-bed RCFE, several of which beds would be “kept open” for patients discharged from LHH; 4) Ideally, an unstated number of Adult Day Health Care (ADHC) slots for people needing day-care supervision; and 5) Ideally, preschool to foster “intergenerational connections” between the elderly and two- to three-year-old preschoolers.

It’s likely to be another proposal that turns out to be dead on arrival.

Although Yee indicated he’s proposing a really small RCFE of 30 beds (that will barely create a dent in the RCFE shortage Citywide) he didn’t indicate how many independent housing and assisted living units he was proposing, or the number of ADHC slots and the size of a preschool, or how they would all be crammed onto LHH’s campus that MOHCD had previously ruled out, indicating LHH was too small of a site for multiple uses.

LHH voluntarily suspended it’s licensed “outpatient” ADHC serving about 60 people daily on March 20, 2009 (possibly down from 100 people previously) but continued paying state licensing fees from November 16, 2009 through June 30, 2013. LHH allowed the license to expire on November 15, 2013 without transferring or selling the license to another agency. At least 91 ADHC clients — including ten people with Alzheimer’s — were impacted by LHH’s ADHC closure.

LHH voluntarily suspended it’s licensed “outpatient” ADHC serving about 60 people daily on March 20, 2009 (possibly down from 100 people previously) but continued paying state licensing fees from November 16, 2009 through June 30, 2013. LHH allowed the license to expire on November 15, 2013 without transferring or selling the license to another agency. At least 91 ADHC clients — including ten people with Alzheimer’s — were impacted by LHH’s ADHC closure.

On January 6, 2009 San Francisco’s Health Commission heard a budget-neutral proposal to keep LHH’s ADHC, a proposal endorsed by LHH’s then-Executive Director John Kanaley who claimed an ADHC would be included in the LHH replacement hospital (which never happened and wasn’t included in the blueprints for the new building). Then-Mayor Gavin Newsom was adamant that his mid-year budget cuts include the closing of LHH’s ADHC, and the Health Commission failed to adopt a Resolution to keep LHH’s ADHC funded. Newsom was also responsible in large measure for eliminating 420 of LHH’s skilled nursing beds in the replacement hospital facility, although he did advocate for building assisted living units on LHH’s campus.

After suing the City twice in November 2004 and again in February 2008 in public-health public-interest lawsuits in which I stood to earn not one penny over the reduction in the number of beds in the rebuild of Laguna Honda Hospital, I became a formal whistleblower in January 2009, reporting to the City Controller’s Whistleblower Program and to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division that closure of LHH’s ADHC program was a probable violation of a DOJ settlement agreement reached with the City of San Francisco.

The California Department of Public Health confirmed in February 2019 in response to a public records request that San Francisco had 20 licensed ADHC’s in 2009, but only 13 licensed ADHC’s a decade later in 2019, a 35% change loss in the number of ADHC facilities. Those facilities had a total of licensed 1,808 participant slots in 2009, which dropped to just 1,323 participants slots in 2019, a 26.8% change loss of 485 participant slots in outpatient capacity.

Among the lost ADHC participant slots were 60 slots at LHH, and a total loss of 170 participant slots at three separate On Loc Senior Health locations (on Mission Street, Geary Boulevard, and Montgomery Street) , totaling 230 (47.7%) of the 485 lost ADHC participant slots between the two organizations.

Among the lost ADHC participant slots were 60 slots at LHH, and a total loss of 170 participant slots at three separate On Loc Senior Health locations (on Mission Street, Geary Boulevard, and Montgomery Street) , totaling 230 (47.7%) of the 485 lost ADHC participant slots between the two organizations.

In my August 27, 2007 public comment, “Flaws in the Glass,” the Draft Assisted Living Feasibility Study for LHH’s campus noted then- Mayor Gavin Newsom supported the assisted living component of the LHH Replacement Project.

In a letter dated August 2, 2007 to community members, Mayor Newsom wrote:

“As I have indicated at numerous community meetings in District 7, I support Laguna Honda continuing its proud tradition as a medically licensed facility providing assisted living units for those in need of medical services. As you know, this model of care is designed to provide maximum independence to medically diagnosed individuals who require some assistance in their daily lives.

Along those lines, I do not support any future placement of supportive housing for the formerly homeless at Laguna Honda Hospital. While I believe that more of this type of housing can help address our homeless problem in a lasting way, Laguna Honda Hospital is an inappropriate location for this housing and [it] should remain an assisted care facility.”

If Supervisor Yee is successful getting the Mayor’s Office of Housing to support independent senior housing on LHH’s campus, MOHCD’s policy is to set aside 20% to 30% of all new housing for people who are homeless.

If Supervisor Yee is successful getting the Mayor’s Office of Housing to support independent senior housing on LHH’s campus, MOHCD’s policy is to set aside 20% to 30% of all new housing for people who are homeless.

Yee’s position paper acknowledges many older adults will eventually need to move to skilled nursing facilities due to increased mobility impairments and chronic medical issues, but his position paper doesn’t discuss increasing the severe shortage of SNF beds in-county by building more SNF units on LHH’s campus or elsewhere in the City.

In fact, Yee’s December 2018 position paper explicitly states in paragraph 5 that the “bleeding of [assisted living] beds continues to this day, without any plans for the City to address this issue.” That’s in the same paragraph in which Yee acknowledges both “low- and middle-income residents are being placed out-of-county.” Clearly Yee is aware that the City has no plans and the out-of-county patient dumping are both huge problems.

Yee’s grand plan for LHH’s campus will be vigorously opposed by the Dignity Fund and the Mayor’s Long-Term Care Coordinating Council (LTCCC), whose shared members vigorously opposed building any more healthcare-related units on LHH’s campus in 2007. Why would they support it now? The language of the Dignity Fund prohibits using those funds for any healthcare services or for senior housing.

Yee’s grand plan for LHH’s campus will be vigorously opposed by the Dignity Fund and the Mayor’s Long-Term Care Coordinating Council (LTCCC), whose shared members vigorously opposed building any more healthcare-related units on LHH’s campus in 2007. Why would they support it now? The language of the Dignity Fund prohibits using those funds for any healthcare services or for senior housing.

Thirteen days after Yee issued his December 2018 position paper, an Assisted Living Workgroup — a group Yee formed in April 2018 with DPH and the Department of Aging and Adult Services (DAAS) — presented recommendations on January 10, 2019 to the LTCCC. The report primarily recommended  that Adult Living Facilities (ALF) — including RCFE’s and Adult Residential Facilities (ARF) for people in between ages 18 and 60 — should be supported by the City in smaller six-bed facilities using subsidies, despite the report noting the model is economically unsupportable and the facilities will likely continue disappearing.

that Adult Living Facilities (ALF) — including RCFE’s and Adult Residential Facilities (ARF) for people in between ages 18 and 60 — should be supported by the City in smaller six-bed facilities using subsidies, despite the report noting the model is economically unsupportable and the facilities will likely continue disappearing.

A vague reference to “alternative models” wasn’t explained, nor was there any mention of expanding the supply of new facilities that the City has been “exploring” and studying “alternative  models” of — for decades — without any meaningful results. It could take decades to build or renovate enough six-bed RCFE’s to make a dent in the shortage of in-county RCFE’s.

models” of — for decades — without any meaningful results. It could take decades to build or renovate enough six-bed RCFE’s to make a dent in the shortage of in-county RCFE’s.

Remarkably, Yee’s Assisted Living Workgroup’s report clearly noted a damning admission: “… Data to document demand is limited, and systems are typically not set up to document the need” for various services.

Multiple Assisted Living Waiver Problems Continue

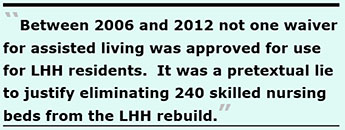

There are several problems Yee needs to address, starting with the lie in 2006 that assisted living waivers would be given to residents of Laguna Honda Hospital who wished to return to living in the community. Between 2006 and 2012 — two years after the LHH replacement hospital was opened in 2010 — not one assisted living waiver had been approved for use for LHH residents or anyone else in San Francisco. It was a pretextual lie to justify eliminating, and never building, 240 skilled nursing beds during the LHH rebuild. San Franciscans were duped and lied to.

Promised Assisted Living Waivers Haven’t Materialized

Promised Assisted Living Waivers Haven’t Materialized

If you’re middle-income and not eligible for Medi-Cal you can’t access the assisted living waiver program as an alternative to being admitted to a SNF. And if you’re not an “in-network” client of San Francisco’s Department of Public Health, you can’t access the State’s assisted living waiver program, either. Nobody on the LTCCC or in Supervisor Yee’s Assisted Living Workgroup talks about this restriction.

The waiver program is essentially a healthcare “silo” reserved for DPH clients who are Medi-Cal eligible. DPH appears to covet, and wants to protect, having that silo unto itself that no other agency should be allowed to encroach on.

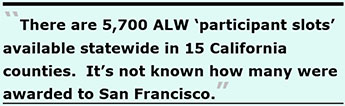

In California, Medi-Cal funds assisted living only through the Assisted Living Waiver (ALW) program. The Workgroup is advocating that the Assisted Living Waiver Program be expanded, an effort they’ve advocated for years, but which hasn’t happened. Currently there are 5,700 ALW “participant slots” available statewide in 15 California counties. It’s not known (yet) how many of the 5,700 ALW slots were awarded to San Francisco when the pilot program was first introduced for just three counties, or how many participant slots may have been increased in San Francisco across the years.

In California, Medi-Cal funds assisted living only through the Assisted Living Waiver (ALW) program. The Workgroup is advocating that the Assisted Living Waiver Program be expanded, an effort they’ve advocated for years, but which hasn’t happened. Currently there are 5,700 ALW “participant slots” available statewide in 15 California counties. It’s not known (yet) how many of the 5,700 ALW slots were awarded to San Francisco when the pilot program was first introduced for just three counties, or how many participant slots may have been increased in San Francisco across the years.

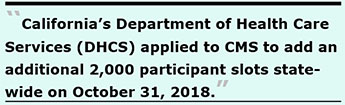

The ALW program is covered by the Social Security Act, and waivers are granted by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS). California’s Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) applied to add an additional 2,000 participant slots, apparently statewide in its October 31, 2018 application to CMS to renew the waiver program for five-year-period 2019 to 2024. It’s unclear how many of the 2,000 will be allocated to San Francisco.

The ALW program is covered by the Social Security Act, and waivers are granted by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS). California’s Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) applied to add an additional 2,000 participant slots, apparently statewide in its October 31, 2018 application to CMS to renew the waiver program for five-year-period 2019 to 2024. It’s unclear how many of the 2,000 will be allocated to San Francisco.

There are another 4,000+ Californians currently languishing on the statewide ALW wait list, so it’s clear there are not enough slots to meet current demand, even if DHCS snags the additional 2,000 assisted living waivers in its 2019 application to CMS. Why didn’t DHS request 4,000 additional waiver slots to clear up the current wait list?

Belatedly, when San Francisco’s DPH was pushed for what should be easily available public records data, DPH eventually provided on February 2, 2019 a summary of California’s DHCS 2017 conversion of San Francisco’s Community Living Support Benefit program to the State’s Assisted Living Waiver program.

Belatedly, when San Francisco’s DPH was pushed for what should be easily available public records data, DPH eventually provided on February 2, 2019 a summary of California’s DHCS 2017 conversion of San Francisco’s Community Living Support Benefit program to the State’s Assisted Living Waiver program.

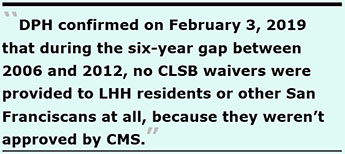

In September 2006, California’s then-Governor Schwarzenegger signed San Francisco’s “Community Living Support Benefit” (CLSB) into law to allow people at risk of nursing home admission to remain living in the community with services and supports funded by the waiver. The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) didn’t approve the CLSB waiver until July 2012 into law. DPH confirmed on February 3, 2019 that during the six-year gap between 2006 and 2012, no CLSB waivers were provided to LHH residents or other San Franciscans at all, because they weren’t approved by CMS.

Five years later, San Francisco’s Department of Public Health decided before June 2017 to not renew its CLSB waiver program. At the time, San Francisco had just 22 participant slots in its CLSB waiver program, although CMS awarded no waivers to San Francisco between 2006 and 2012. It’s not known whether the Mayor’s LTCCC received advance notice beforehand that DPH wasn’t going to renew the City’s CLSB waiver program in June 2017, nor is it known whether Protection and Advocacy, Inc. and other disability rights organizations were informed of DPH’s decision to drop its CLSB program, after reaching the Mark Chambers settlement agreement with the DOJ in 2006.

Five years later, San Francisco’s Department of Public Health decided before June 2017 to not renew its CLSB waiver program. At the time, San Francisco had just 22 participant slots in its CLSB waiver program, although CMS awarded no waivers to San Francisco between 2006 and 2012. It’s not known whether the Mayor’s LTCCC received advance notice beforehand that DPH wasn’t going to renew the City’s CLSB waiver program in June 2017, nor is it known whether Protection and Advocacy, Inc. and other disability rights organizations were informed of DPH’s decision to drop its CLSB program, after reaching the Mark Chambers settlement agreement with the DOJ in 2006.

The 2019 Summary shows that the initial San Francisco CLSB waiver limited DPH’s ability to contract with assisted living facilities (ALF's) in San Francisco County; as a result, DPH initially relied upon contracted assisted living facilities out-of-county (more out-of-county patient dumping during that six-year period). DPH hasn’t indicated how many of the 22 initial slots were placed in out-of-county facilities.

The 2019 Summary shows that the initial San Francisco CLSB waiver limited DPH’s ability to contract with assisted living facilities (ALF's) in San Francisco County; as a result, DPH initially relied upon contracted assisted living facilities out-of-county (more out-of-county patient dumping during that six-year period). DPH hasn’t indicated how many of the 22 initial slots were placed in out-of-county facilities.

The CLSB program was shifted to California’s Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) for the replacement Assisted Living Waiver (ALW) program now authorized by CMS, adding another 22 participant slots, for a total of 44 slots purportedly allocated to San Francisco County. It’s not clear if the 44 ALW slots were ever actually assigned to San Francisco County

Now, wait lists for all 44 of San Francisco’s Assisted Living Waivers are completely managed by the State, rather than by local control! And once on the wait list, people languish on it for two years, or more, as they do all over the state.

Now, wait lists for all 44 of San Francisco’s Assisted Living Waivers are completely managed by the State, rather than by local control! And once on the wait list, people languish on it for two years, or more, as they do all over the state.

No wonder that Supervisor Yee’s Assisted Living Workgroup — including DPH and DAAS — recommended in its January 20, 2019 “Findings and Recommendations” that management of the ALW program be shifted from regional or State control to local management. Which is an odd recommendation, because if in June 2017 DPH decided it didn’t have the resources to manage the first CLSB 22 waivers, what makes Yee’s  Workgroup think that the City can manage 44 or more slots now?

Workgroup think that the City can manage 44 or more slots now?

One astute observer noted that 15 of San Francisco’s current 44 ALW waivers appear to have been awarded to a behavioral health facility, leading some observers to suspect the program may be trying to stay out of healthcare for elderly people who have geriatric and chronic health problems, focusing only on people with behavioral problems.

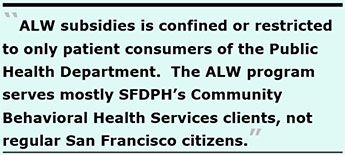

Another astute observer who spoke on condition of anonymity noted that what is missing is access by the general public in San Francisco to ALW subsidies or waivers, since access is confined or restricted to only patient consumers of the Public Health Department. The ALW program serves mostly DPH’s Community Behavioral Health Services clients, not regular San Francisco citizens. So, if you’re not a Medi-Cal client, not an in-network client of DPH’s Community Health network, and you’re not a DPH Behavioral Health Services client, you’re not likely going to obtain an assisted living waiver slot.

Claims of Number of Assisted Living Waivers Granted to San Francisco May Be Another Myth

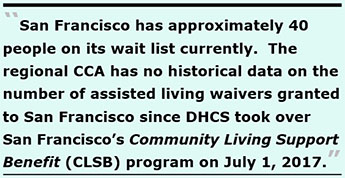

On Friday, February 1, two records requests were placed regarding the historical and current number and utilization rates of Assisted Living Waivers assigned to San Francisco. One records request was placed to DHCS, which didn’t acknowledge receipt of the records request, or respond providing the requested data.

On Friday, February 1, two records requests were placed regarding the historical and current number and utilization rates of Assisted Living Waivers assigned to San Francisco. One records request was placed to DHCS, which didn’t acknowledge receipt of the records request, or respond providing the requested data.

Unlike Los Vegas, what was purportedly granted to San Francisco may not have actually stayed in San Francisco.

The second records request February 1 was submitted to Ms. Stephanie Collins, California’s ALW Program Coordinator for the Sacramento, San Joaquin, and San Francisco county jurisdictions. Collins is an employee of Blossom Ridge Home Health Agency, doing business with DHCS as Ridge Care Coordinating Agency, a non-profit designated by the state to  be the regional coordinating Care Coordinator Agency (CCA) for all three counties. Collins phoned me, rather than responding by e-mail, the following Monday, February 4.

be the regional coordinating Care Coordinator Agency (CCA) for all three counties. Collins phoned me, rather than responding by e-mail, the following Monday, February 4.

Collins shared:

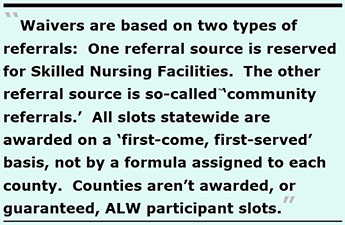

Monthly, DHCS provides each regional CCA a new number of ALW slots approved and released for each CCA jurisdiction from the statewide wait list. Wait list decisions aren’t made by each CCA; they do what the state tells them to do.

Monthly, DHCS provides each regional CCA a new number of ALW slots approved and released for each CCA jurisdiction from the statewide wait list. Wait list decisions aren’t made by each CCA; they do what the state tells them to do. granted to San Francisco since DHCS took over San Francisco’s Community Living Support Benefit (CLSB) program on July 1, 2017, no data about the number of San Franciscans wait-listed over the years or an average length of time on the wait list, and no data on mortality rates of those who applied for an assisted living waiver but who died before receiving a waiver.

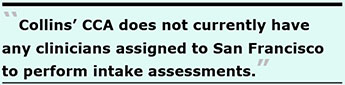

granted to San Francisco since DHCS took over San Francisco’s Community Living Support Benefit (CLSB) program on July 1, 2017, no data about the number of San Franciscans wait-listed over the years or an average length of time on the wait list, and no data on mortality rates of those who applied for an assisted living waiver but who died before receiving a waiver. Collins’ CCA does not currently have any clinicians assigned to San Francisco to perform intake, and other types of, assessments for ALW applicants and clients.

Collins’ CCA does not currently have any clinicians assigned to San Francisco to perform intake, and other types of, assessments for ALW applicants and clients.Should Yee’s Assisted Living Workgroup succeed in efforts to move decision-making from the state level to local control, the first thing that needs to be addressed is ensuring San Francisco receives a dedicated number of ALW slots each funding cycle, and the second thing requiring attention is addressing whether wait lists in-county are distributed among the two types of referring sources, not on a “first-come, first-served” basis across both sources combined.

DHCS confirmed on February 14, 2019 that of the 22 people enrolled in San Francisco’s CLSB program, only four transitioned to the State’s ALW program in August 2017. The remaining 18 and the 20 ALW slots purportedly assigned to San Francisco were re-allocated to the ALW program statewide.

DHCS confirmed on February 14, 2019 that of the 22 people enrolled in San Francisco’s CLSB program, only four transitioned to the State’s ALW program in August 2017. The remaining 18 and the 20 ALW slots purportedly assigned to San Francisco were re-allocated to the ALW program statewide.

State Assembly and Board of Supervisors a Day Late and a Dollar Short

As noted, DHCS submitted its application to CMS requesting to add an additional 2,000 ALW participant slots statewide on October 31, 2018.

As noted, DHCS submitted its application to CMS requesting to add an additional 2,000 ALW participant slots statewide on October 31, 2018.

So, when State Assembly Member Ash Kalra (D–Assembly District 27) introduced Assembly Bill 50 on December 3, 2018 directing DHCS to submit a request for CMS’ ALW Spring 2019 five-year renewal period to expand California’s ALW program to 18,500 participant slots — adding 13,000 more slots, not 2,000 — the State Assembly was already a day late and a dollar short, because the application had already been submitted by DHCS to CMS over a month before. Kalra’s bill also stipulated that before submitting the application to CMS that a draft of DHCS’ proposed renewal application should be released for stakeholder comment.

Fast forward to February 5, 2019 when Supervisors Yee and Rafael Mandelman introduced a Resolution (File No. 190155) urging the Board of Supervisors to support AB 50 to expand the ALW program for Medi-Cal beneficiaries and advocate that a greater number of slots be allocated to San Francisco County. Their Resolution was heard the following Tuesday on February 12.

The Board of Supervisors Resolution was also a day late and a dollar short, being passed more than three months after DHCS had already submitted its application to CMS. The Resolution was passed February 12 despite drafting errors.

Assembly Member Kalra’s AB 50 didn’t mention anything about changing administration of the ALW program from State control to local jurisdiction control, as Supervisor Yee’s Assisted Living Workgroup recommended in the Workgroup’s January 10, 2019 recommendations.

Assembly Member Kalra’s AB 50 didn’t mention anything about changing administration of the ALW program from State control to local jurisdiction control, as Supervisor Yee’s Assisted Living Workgroup recommended in the Workgroup’s January 10, 2019 recommendations.

Yee’s Resolution should have been amended to include advocating with the State legislature that SB 50 incorporate transitioning the waiver program to full local control.

But the Resolution was passed on February 12 without additional amendments as part of the Board’s four-item package of issues introduced for adoption without committee reference (i.e., without having been heard at a committee level). There was no debate, or any comments made by the Board of Supervisors before passing Yee’s resolution to support AB 50.

What's the Heath Care Services Master Plan Got to Do With It?

The City’s Health Care Services Master Plan (HCSMP) is a long-range policy document developed collaboratively between the Public Health Department and the Planning Department, because it involves land-use issues of interest to both City departments. It’s intended to improve community health and access to healthcare, particularly for San Francisco’s most vulnerable. The purpose of the plan is to identify current and projected needs, and locations for health care services, particularly for “vulnerable populations.”

The City’s Health Care Services Master Plan (HCSMP) is a long-range policy document developed collaboratively between the Public Health Department and the Planning Department, because it involves land-use issues of interest to both City departments. It’s intended to improve community health and access to healthcare, particularly for San Francisco’s most vulnerable. The purpose of the plan is to identify current and projected needs, and locations for health care services, particularly for “vulnerable populations.”

The HCSMP Ordinance became law in December 2010 and was to be updated every three years. Between July 2011 and June 2013, the first Plan was developed, which went into effect in December 2013. A planned update was to happen in the Summer of 2016, and although a three-year plan update was initiated and was due in 2017, it still hasn’t been written or concluded as of February 2019. It’s nearly three years late already.

The Plan is supposed to assess healthcare facility capacity across the City, including an assessment of gaps in facilities and services. The Plan aims to focus on developing high-priority healthcare facilities, including both skilled nursing facilities and other long-term care facilities and services.

Back in 2013, the Department of Public Health and the Planning Department jointly developed a Health Care Services Master Plan (HCSMP). But there was no section in the Plan to focus on long-term care healthcare services in the City, which has been under the control of the Mayor’s LTCCC that has shirked its duty to provide meaningful long-term care programs to include chronic disease management for people unable to live independently and safely in the community, offering instead only limited “supports” and subsidies to help them.

The HCSMP is now being updated by DPH and the Planning Department. The Board of Supervisors should ensure that this time around the Plan include meaningful planning for long-term care services to prevent out-of-county discharges.

The HCSMP is now being updated by DPH and the Planning Department. The Board of Supervisors should ensure that this time around the Plan include meaningful planning for long-term care services to prevent out-of-county discharges.

This ties in, in part, to Yee’s efforts to expand Residential Care Facilities for the Elderly capacity and other housing on the campus of Laguna Honda Hospital.

Unfortunately, working on development of the HCSMP has been stalled, in part, by the ouster of the Director of Public Health, Barbara Garcia.

The San Francisco Examiner reported on August 23, 2018 that Garcia resigned as director of the Department of Public Health the day before on August 22. She was given a choice to be fired or resign for having steered a City contract to her domestic partner. That halted Garcia’s attempts to locate space for a sub-acute unit in any other City hospital. Without Garcia’s leadership to establish a new sub-acute unit in an existing acute-care hospital in the City to replace the one St. Luke’s closed, you can almost guarantee the number of out-of-county discharges between November 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019 will increase significantly.

Five months after Garcia’s ouster, the Health Commission reportedly had few candidates willing to even apply for the job, which remained vacant until January 31 when Mayor Breed announced the new Director of Public Health, an insider. We’ll see if he picks up Garcia’s leadership where she left off in trying to expand SNF- and sub-acute care units in existing, underutilized private-sector hospital space, and her efforts to get the HCSMP updated and finished.

Lack of Data No Surprise!

As the Westside Observer reported in May 2017 (“Where’s Our Torchbearer for the Elderly?”), the Board of Supervisors Budget and Legislative Analyst (BLA) issued a report in July 2016 (“Audit of Senior Services in San Francisco”) highly critical that DAAS has failed for years to conduct meaningful data collection via a gap analysis.

A Gap Analysis estimates unmet needs for particular services — the gap between the number of individuals currently receiving a service and the total population that might benefit from a particular service. Without a robust Gap Analysis, DAAS (and DPH) lack critical information during decision-making.

A Gap Analysis estimates unmet needs for particular services — the gap between the number of individuals currently receiving a service and the total population that might benefit from a particular service. Without a robust Gap Analysis, DAAS (and DPH) lack critical information during decision-making.

The BLA’s performance audit included Table 1.2, Gap Ratings for Senior Service Areas (Rapid City, SD) as an example. The Rapid City gap analysis includes expressed needs and preferences for assisted living and skilled nursing facility care.

The BLA wants DAAS and perhaps DPH to conduct meaningful gap analyses. The Planning Department wants a healthcare services gap analysis for the HCSMP around zoning issues. Why is San Francisco refusing to perform gap analyses across multiple City departments? Will Supervisor Yee lead on the issue of getting these multiple gap analyses conducted now that he’s Board president?

Ombudsman Benson Nadell’s Concerns

Benson Nadell, a State employee who is San Francisco’s Long-Term Care Ombudsman advocating for patients, and who investigates complaints of abuse in the City’s SNF’s, assisted living, and board-and-care facilities remains concerned. He’s held that job for decades and has “institutional memory” of the various problems facing elderly and disabled San Franciscans. He’s served on the Mayor’s Long-Term Care Coordinating Council (LTCCC) since its inception in 2007.

Benson Nadell, a State employee who is San Francisco’s Long-Term Care Ombudsman advocating for patients, and who investigates complaints of abuse in the City’s SNF’s, assisted living, and board-and-care facilities remains concerned. He’s held that job for decades and has “institutional memory” of the various problems facing elderly and disabled San Franciscans. He’s served on the Mayor’s Long-Term Care Coordinating Council (LTCCC) since its inception in 2007.

On January 2, 2018 Nadell presented testimony about how omissions and shortsightedness in collecting data affects developing public policy. The problem? Missing data. No data is asked for, none collected. The City doesn’t ask for data. No questions, no data.

He noted:

“Data can only flow from existing data. Until the right questions are asked by City and County leaders, long-term care policy will be skewed towards those questions that are asked. Data will always be missing in this context.”

Nadell notes that among the questions that are not asked includes such things as:

Nadell notes that among the questions that are not asked includes such things as:

Previously, Nadell presented testimony December 7, 2017 that sub-acute care is not post-acute care, observing:

[A policy was set in August 2007] “for the duration of the two Settlement Agreements where an affordable low income RCFE Assisted Living [units] would not be invested in as a resolution to housing for those discharged from LHH or any other SNF. The City missed the chance to solve this lack of RCFE. Instead the shift was to rental subsidies from the city.”

Before that, Nadell presented testimony September 5, 2017 about St. Luke’s Sub-Acute SNF Closure, in which he noted the Mayor’s LTCCC was enthralled and under the spell of the social model of care in home- and community-based alternative settings. He’s realized this is a matter about people who have complex medical conditions and need round-the-clock care and custodial care for chronic illnesses and disease management.

Before that, Nadell presented testimony September 5, 2017 about St. Luke’s Sub-Acute SNF Closure, in which he noted the Mayor’s LTCCC was enthralled and under the spell of the social model of care in home- and community-based alternative settings. He’s realized this is a matter about people who have complex medical conditions and need round-the-clock care and custodial care for chronic illnesses and disease management.

The Hospital Council of Northern California has partnered with the Health Commission, the San Francisco Department of Public, and the City’s Department of Aging and Adult Services (DAAS) for three years, since at least February 2016, entrenched in searching for solutions to the City’s “Post-Acute Care Challenge.” No demonstrable results have surfaced.

Nadell noted September 5, 2017 that “post-acute care is not long-term care or focused on chronic disease management.” San Francisco’s “post-acute care” challenge ignores that complex medical coordination is long-term care based on management of chronic illnesses. Nadell also reminded policymakers that they should not confuse sub-acute care with post-acute care.

CANHR: Concerns About RCFE’s, Assisted Living Facilities, and CCRC’s Lack of Focus on Healthcare

In early January 2018, the California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform (CANHR) issued a blistering report noting that during the past 20 years residents of RCFE’s are “older, sicker, and have more complex medical and care needs,” and RCFE’s now resemble nursing homes of years past. CANHR’s report notes the outdated “social model of care” (favored by San Francisco’s disability rights advocates, the Dignity Fund, and the LTCCC) has all but ignored the health care needs of RCFE and assisted living clients whose acuity levels have worsened. The CANHR report is very critical of Continuing Care Retirement Communities — such as the “Life Care Facility” Yee is proposing for LHH’s campus — for not focusing on provision of healthcare facilities.

In early January 2018, the California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform (CANHR) issued a blistering report noting that during the past 20 years residents of RCFE’s are “older, sicker, and have more complex medical and care needs,” and RCFE’s now resemble nursing homes of years past. CANHR’s report notes the outdated “social model of care” (favored by San Francisco’s disability rights advocates, the Dignity Fund, and the LTCCC) has all but ignored the health care needs of RCFE and assisted living clients whose acuity levels have worsened. The CANHR report is very critical of Continuing Care Retirement Communities — such as the “Life Care Facility” Yee is proposing for LHH’s campus — for not focusing on provision of healthcare facilities.

CANHR believes that RCFE’s are unsafe for consumers, given that 1) RCFE’s’ are essentially unregulated and unaccountable for their actions in California, 2) Minimal staffing requirements for RCFE’s are nonexistent, and 3) RCFE’s have total discretion to increase rates and assess additional charges.

CANHR believes that RCFE’s are unsafe for consumers, given that 1) RCFE’s’ are essentially unregulated and unaccountable for their actions in California, 2) Minimal staffing requirements for RCFE’s are nonexistent, and 3) RCFE’s have total discretion to increase rates and assess additional charges.

CANHR notes that the Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) program in California — including the paltry number of Assisted Living Waivers statewide — are difficult to access due to 1) Limited slots, 2) Strict enrollment caps, and 3) Waitlists that are over two-years years long. Many frail and elderly adults may die while waiting for a slot to HCBS programs.

Focus on Data Collection!

As noted in (“Torchbearer”) in May 2017, the absolute hatred exhibited by the LTCCC, Community Living Fund, and Dignity Fund in providing skilled nursing facility care to elderly and disabled people who may actually prefer an institutional setting is symptomatic of a lack of empathy for vulnerable patients’ choices for those who choose to receive their care in long-term care, skilled nursing facilities in-county.

What these organizations fail to measure, they can’t accurately assess. Nor can they fix it, particularly without gap analyses measuring client preferences.

Yee needs to expand his focus to include SNF and long-term care facilities in addition to RCFE’s and assisted living facilities, and he needs to do so citywide, not just on LHH’s campus.

Yee needs to expand his focus to include SNF and long-term care facilities in addition to RCFE’s and assisted living facilities, and he needs to do so citywide, not just on LHH’s campus.

And the Board of Supervisors — under Yee’s leadership — must mandate that private-sector hospitals report their out-of-county discharge data to DPH. How many San Franciscans have already been discharged out-of-county isn’t known.

Also, back in August 2018, both Supervisor Yee and other Supervisors — who agreed in principle to be co-sponsors — were asked to quickly introduce legislation requiring each and every private-sector and public-sector hospital in the City,  and also RCFE facilities, to report out-of-county discharge information, including a limited amount of demographic data, to DPH annually going forward. In the five months since, no legislation has been forthcoming from Yee’s Office. Why not?

and also RCFE facilities, to report out-of-county discharge information, including a limited amount of demographic data, to DPH annually going forward. In the five months since, no legislation has been forthcoming from Yee’s Office. Why not?

Why is Yee reluctant to collect the out-of-county discharge data? Couldn’t he have introduced such legislation by now?

As Dr. Teresa Palmer, a geriatrician who worked at LHH for over 20 years notes, “If we don’t know how many folks have been forced to leave the county for long-term care, how can we plan for what San Franciscans need if we don’t collect the relevant data?”

As Dr. Teresa Palmer, a geriatrician who worked at LHH for over 20 years notes, “If we don’t know how many folks have been forced to leave the county for long-term care, how can we plan for what San Franciscans need if we don’t collect the relevant data?”

Supervisor Yee should use his bully pulpit as Board president to grow the funding pie and fund a range of facilities, including SNF’s, RCFE’s, ADHC, and independent residential senior housing, not pit them one against each other since all are critically-needed, urgent priorities the City should fund — to stop the plague of out-of-county discharges and patient dumping.

Is What's Past, Prologue?

Is What's Past, Prologue?

Given San Francisco’s past history going back a dozen or more years to 2006 and the City’s failure to maintain a sufficient amount of in-county facilities for elderly and disabled San Franciscans, is that the prologue of what Board President Yee will settle for?

Monette-Shaw is a columnist for San Francisco’s Westside Observer newspaper, and a member of the California First Amendment Coalition (FAC) and the ACLU. He operates stopLHHdownsize.com. Contact him at monette-shaw@westsideobserver.com.