Article in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Article in Print Printer-friendly PDF fileWestside Observer Newspaper

July 2017 at www.WestsideObserver.com

“Oversight Committee” Provides Scant oversight

Part 2:

CGOBOC's Other CSA Duties as CARB

Article in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Article in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Westside Observer

Newspaper

July 2017 at www.WestsideObserver.com

“Oversight Committee” Provides Scant oversight

Part 2:

CGOBOC's Other CSA Duties as CARB

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

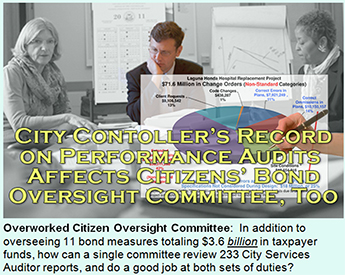

The first part of this two-part article examined how the Citizens’ General Obligation Bond Oversight Committee’s (CGOBOC) failure to adequately examine construction project change orders may lead to project cost overruns, or reduction in the scope of bond-funded construction projects.

That first article questioned whether CGOBOC has had too many duties piled on to its workload, and whether a second citizens’ committee should be formed to focus on the additional duties assigned to CGOBOC in 2003, so CGOBOC can return to focusing only on oversight of general obligation bonds, as it had been created to do in 2002.

That first article questioned whether CGOBOC has had too many duties piled on to its workload, and whether a second citizens’ committee should be formed to focus on the additional duties assigned to CGOBOC in 2003, so CGOBOC can return to focusing only on oversight of general obligation bonds, as it had been created to do in 2002.

When voters passed a ballot measure in 2003 to create the City Services Auditor (CSA) program housed in the City Controller’s Office, CGOBOC was handed additional duties as the Citizen’s Audit Review Board, and also assigned to oversee the City Controller’s whistleblower program.

CGOBOC Oversight of the Whistleblower Program

CGOBOC has done little more than review quarterly, or semi-annual, or annual Whistleblower reports authored by the Controller’s Office. To be fair, behind the scenes CGOBOC’s liaisons to the Controller’s whistleblower program say that they meet with whistleblower investigators to review procedures. The liaisons seem to find the Controller’s whistleblower program staff to be “professional,” but the entire review and oversight of whistleblower complaints is veiled under a total cloak of confidentiality. The liaisons may be doing a fair job, but we don’t know for certain. They appear to have done the best they can, given that their main job of bond oversight is enormous.

CGOBOC has done little more than review quarterly, or semi-annual, or annual Whistleblower reports authored by the Controller’s Office. To be fair, behind the scenes CGOBOC’s liaisons to the Controller’s whistleblower program say that they meet with whistleblower investigators to review procedures. The liaisons seem to find the Controller’s whistleblower program staff to be “professional,” but the entire review and oversight of whistleblower complaints is veiled under a total cloak of confidentiality. The liaisons may be doing a fair job, but we don’t know for certain. They appear to have done the best they can, given that their main job of bond oversight is enormous.

CGOBOC has only rarely asked any detailed questions about the Controller’s whistleblower reports, and CGOBOC has never called for a review of any specific whistleblower complaint. Nor has CGOBOC ever held detailed public discussions about the City Controller’s disposition of individual whistleblower complaints. Despite appointing a CGOBOC member as a liaison to the Controller’s whistleblower program, liaisons have rarely provided any meaningful updates during CGOBOC meetings about their inquiries into the whistleblower program.

CGOBOC has included just scant information about its oversight of the whistleblower program in its Annual Reports. Its Annual Report for FY 2015–2016 contained just a single paragraph from its whistleblower liaisons, including a sentence that read: “To the best of our knowledge based on our activities, we believe the [Controller’s] whistleblower program continues to operate in an effective and efficient manner.”

But its annual report for 2014–2015 was slightly more critical, when it reported CGOBOC had advocated for implementation of a whistleblower satisfaction survey, but admitted there were too few survey responses to draw any conclusions. That annual report also all but admitted CGOBOC had not examined whistleblower complaints that may have involved retaliation against a City employee who had alleged retaliation occurred, and also noted that given the Civil Grand Jury’s report about the City’s whistleblower protection ordinance (WPO), its whistleblower liaison concluded that “certain sections of the WPO, do, on the surface, appear to warrant review and possibly revision.”

But its annual report for 2014–2015 was slightly more critical, when it reported CGOBOC had advocated for implementation of a whistleblower satisfaction survey, but admitted there were too few survey responses to draw any conclusions. That annual report also all but admitted CGOBOC had not examined whistleblower complaints that may have involved retaliation against a City employee who had alleged retaliation occurred, and also noted that given the Civil Grand Jury’s report about the City’s whistleblower protection ordinance (WPO), its whistleblower liaison concluded that “certain sections of the WPO, do, on the surface, appear to warrant review and possibly revision.”

CGOBOC has apparently failed to correlate whether any whistleblower complaints dismissed (or possibly sustained) where a whistleblower subsequently went on to file a lawsuit in court in which the whistleblower prevailed and was awarded substantial legal settlements ever occurred. One such whistleblower is Dr. Derek Kerr, a 20-year senior physician at Laguna Honda Hospital who had filed multiple whistleblower complaints, sued in court for wrongful termination, and was awarded $750,000 in a settlement and court expenses.

CGOBOC should direct that the City Controller’s whistleblower program staff coordinate with the City Attorney’s Office to review confidentially the names of employees who had filed whistleblower complaints and correlate those names with the names of City employees who later went on to file lawsuits against the City. After all, Kerr frequently testifies during CGOBOC meetings and is known to CGOBOC members as one such whistleblower who prevailed in court. How hard could it have been to correlate whistleblower complainant names with the names of plaintiffs who filed lawsuits to increase CGOBOC’s “oversight” of the Controller’s whistleblower program?

CGOBOC should direct that the City Controller’s whistleblower program staff coordinate with the City Attorney’s Office to review confidentially the names of employees who had filed whistleblower complaints and correlate those names with the names of City employees who later went on to file lawsuits against the City. After all, Kerr frequently testifies during CGOBOC meetings and is known to CGOBOC members as one such whistleblower who prevailed in court. How hard could it have been to correlate whistleblower complainant names with the names of plaintiffs who filed lawsuits to increase CGOBOC’s “oversight” of the Controller’s whistleblower program?

Kerr can’t have been the only City employee who filed a whistleblower complaint, went on to file a lawsuit, and then prevailed in court with a significant settlement award.

Kerr can’t have been the only City employee who filed a whistleblower complaint, went on to file a lawsuit, and then prevailed in court with a significant settlement award.

Also to be fair, some observers believe CGOBOC and the Controller have both been respectful and responsive — after a few years — to citizen input about the whistleblower program, and some things have gotten much better as a result of citizen feedback, including whistleblower staffing, funding, and quality of the Controller’s whistleblower reports.

CGOBOC Oversight of CSA Audits

When voters passed Prop. “C” in November 2003 adding that CGOBOC serve as a Citizens Audit Review Board (CARB) to review all CSA audits, voters ended up opening Pandora’s secrecy box, or a can full of unintended worms.

When voters passed Prop. “C” in November 2003 adding that CGOBOC serve as a Citizens Audit Review Board (CARB) to review all CSA audits, voters ended up opening Pandora’s secrecy box, or a can full of unintended worms.

Prop. “C” called for the CSA unit to monitor the level and effective of services provided by City government to ensure the financial integrity and improve the overall performance and efficiency of City government. A high-level overview of service areas to be audited includes, but was not limited to: Street, sidewalk, and park cleanliness; performance of public works and government-controlled public utilities; transportation, including the MTA; the criminal justice system; fire and paramedic services; public health and human services; city management; and human resources, including personnel and labor relations.

Specifically, Prop. “C” — which was subsequently incorporated as City Charter Appendix “F” — notes in §F1.103, that the CSA Unit shall conduct and publish annual reviews of management and employment practices that either promote or impede effective and efficient operation of City government. Further §F1.104 requires the CSA unit to conduct comprehensive, financial and performance audits of City departments each year, and City services and activities. It is thought that the CSA unit has never performed during the 14 years following its inception any comprehensive financial or performance audits of an entire City Department. The CSA unit should be benchmarking entire City departments against comparable cities. This is required under CSA’s mandates listed in City Charter Appendix “F,” but is not happening.

Specifically, Prop. “C” — which was subsequently incorporated as City Charter Appendix “F” — notes in §F1.103, that the CSA Unit shall conduct and publish annual reviews of management and employment practices that either promote or impede effective and efficient operation of City government. Further §F1.104 requires the CSA unit to conduct comprehensive, financial and performance audits of City departments each year, and City services and activities. It is thought that the CSA unit has never performed during the 14 years following its inception any comprehensive financial or performance audits of an entire City Department. The CSA unit should be benchmarking entire City departments against comparable cities. This is required under CSA’s mandates listed in City Charter Appendix “F,” but is not happening.

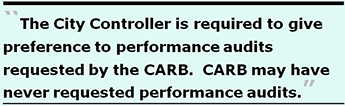

The CSA unit has discretion to select for audit on a rotating basis various City departments and City services, and the City Controller is required to give preference for performance audits requested by CGOBOC acting as the CARB, the Mayor, Board of Supervisors, City department heads, and City commissions. It’s thought CGOBOC — as the CARB — may have never requested specific performance audits of particular programs or any City department.

The CSA unit has discretion to select for audit on a rotating basis various City departments and City services, and the City Controller is required to give preference for performance audits requested by CGOBOC acting as the CARB, the Mayor, Board of Supervisors, City department heads, and City commissions. It’s thought CGOBOC — as the CARB — may have never requested specific performance audits of particular programs or any City department.

I readily admit I have not focused on, or researched, the many issues behind CGOBOC reviewing all CSA audits. But another “usual suspect” at CGOBOC meetings has, in part, focused on the CSA audit oversight issues — a gentleman named Jerry Dratler, who is a former member of both San Francisco’s 2012–2013 and 2014–2015 Civil Grand Jury’s, and is a former member of CGOBOC. Dratler has notable credentials:1

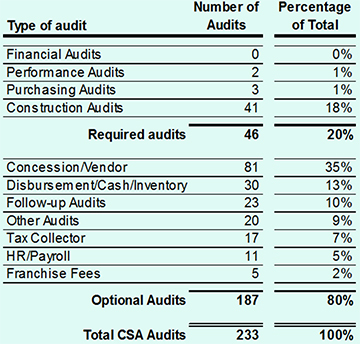

Dratler has documented and submitted testimony to CGOBOC that over the five-year period between February 28, 2012 and January 18, 2017 the Controller’s CSA Unit performed the following types of 233 audits:

Table 1: Summary of CSA Audits, February 2012 – January 2017

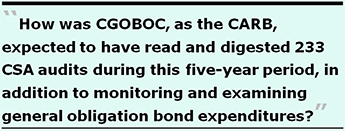

How was CGOBOC — as the CARB — expected to have read and digested 233 CSA audits during this five-year period, in addition to its mandate to monitor and examine general obligation bond expenditures?

How was CGOBOC — as the CARB — expected to have read and digested 233 CSA audits during this five-year period, in addition to its mandate to monitor and examine general obligation bond expenditures?

Dratler is concerned that devoting 80% of all audits to “optional audits” is excessive, and appears to be a misallocation, and a backwards allocation, of audit resources. He’s also concerned that “concessionaire” audits are not required under by City Charter Appendix “F,” and notes that 60 (74%) of the concession audits were for Airport or Port concessionaires. Dratler believes the concessionaire audits are a very large allocation of CSA’s audit budget, and wonders what the findings were from the 60 concession audits. He questions whether the number of concession audits should be increased due to significant audit findings, or whether they should be reduced because of a lack of sufficient audit findings.

Finally, Dratler astutely notes that Charter Appendix §F1.113 states the controller’s audit fund is to be used exclusively to implement duties and requirements of Appendix “F.” Concession audits are not a duty or requirement of Appendix “F.” Finally, he notes §F1.113 appears to prohibit the use of the Controller’s Audit Fund for existing non-audit related functions and, therefore, does not apply to the concession audits.

Finally, Dratler astutely notes that Charter Appendix §F1.113 states the controller’s audit fund is to be used exclusively to implement duties and requirements of Appendix “F.” Concession audits are not a duty or requirement of Appendix “F.” Finally, he notes §F1.113 appears to prohibit the use of the Controller’s Audit Fund for existing non-audit related functions and, therefore, does not apply to the concession audits.

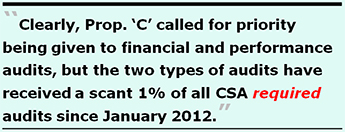

Clearly, Prop. “C” called for priority being given to financial and performance audits, but the two types of audits have received a scant 1% of all CSA required audits since January 2012.

It was initially unclear why Dratler included construction audits as being required audits, because the word “construction” was not mentioned in the legal text of Prop. “C” and searching through City Charter Appendix “F” on-line, the terms “construction” and “construction audits” were also not found among the duties of the CSA. Following up with Dratler, he included the construction audits as “required” audits since Prop. “F” requires certain street, park, and open space audits, most of which involve construction.

It was initially unclear why Dratler included construction audits as being required audits, because the word “construction” was not mentioned in the legal text of Prop. “C” and searching through City Charter Appendix “F” on-line, the terms “construction” and “construction audits” were also not found among the duties of the CSA. Following up with Dratler, he included the construction audits as “required” audits since Prop. “F” requires certain street, park, and open space audits, most of which involve construction.

Dratler provided an extended analysis about the 41 construction audits, which sheds further light. His new analysis shows that 24 (59%) of the 41 audits involved the Airport, PUC, and MTA construction projects — essentially “Optional Audits” — not the required street, park, and open space audits.

Most of the construction audits deal with topics the CSA is not required to audit. While there obviously is some benefits to auditing the MTA or the PUC, they are not streets, parks or open spaces. Only two of the audits dealt with streets, and one was the Cumming external audit of the Road Repaving and Street Safety (RRSS) bond. Only 7% of audits dealt with parks.

The key issue is: CGOBOC is responsible for oversight of the CSA, and CGOBOC is also the Citizens Audit Review Board. CGOBOC is not ensuring CSA audit resources are allocated consistent with the requirements of Charter Appendix “F.”

The key issue is: CGOBOC is responsible for oversight of the CSA, and CGOBOC is also the Citizens Audit Review Board. CGOBOC is not ensuring CSA audit resources are allocated consistent with the requirements of Charter Appendix “F.”

And of all audits, Concessionaire audits have received the highest percentage of CSA audits — every penny owed to City coffers from concessionaire’s apparently meaning greater revenue for the City and deserving of greater attention than financial or performance audits.

The CSA is not meeting requirements established in 2003. CGOBOC is aware audits required by City Charter Appendix “F” aren’t being conducted by the CSA. Why is this allowed to continue?

Over the years, Mr. Dratler has provided thoughtful recommendations on how CGOBOC — acting as the CARB overseeing the CSA function — should better coordinate its own annual work plans with the CSA’s annual work plans. His recommendations — both as a former member of CGOBOC and now as a private citizen — are too detailed and extensive for this article, but are available here for interested readers.

Dratler’s “Risk-Based” Bond Expenditure Review Recommendation

Mr. Dratler submitted a recommendation that CGOBOC adopt a risk-based bond expenditure oversight policy. He argues that CGOBOC identify areas with the highest risk, and devote audit and reporting resources to the high-risk areas first.

Mr. Dratler submitted a recommendation that CGOBOC adopt a risk-based bond expenditure oversight policy. He argues that CGOBOC identify areas with the highest risk, and devote audit and reporting resources to the high-risk areas first.

He argues that:

Change order risk should be managed by reporting and monitoring project changes by the categories of change orders (errors, omissions, client-requested, etc.). Despite this author having prodded CGOBOC to do so since at least 2010, CGOBOC has failed so far to do so.

Change order risk should be managed by reporting and monitoring project changes by the categories of change orders (errors, omissions, client-requested, etc.). Despite this author having prodded CGOBOC to do so since at least 2010, CGOBOC has failed so far to do so. Dratler noted that an external audit performed by Cumming Construction Management on behalf of the CSA found that on the Road Repaving and Street Safety (RRSS) bond, construction management and design costs for curb ramps in the RRSS audit report were 29% of total project costs. Cumming’s opined — beyond scope of the requested audit — that the cost should have been 50% lower, at just 11% to 14% of total project costs.

Dratler noted that an external audit performed by Cumming Construction Management on behalf of the CSA found that on the Road Repaving and Street Safety (RRSS) bond, construction management and design costs for curb ramps in the RRSS audit report were 29% of total project costs. Cumming’s opined — beyond scope of the requested audit — that the cost should have been 50% lower, at just 11% to 14% of total project costs. Design costs for the Earthquake Safety and Emergency Response (ESER) bond were $30.6 million (16.1%) of total project costs. Another Cumming’s audit report — again beyond the scope of the requested audit — opined the design costs should have been 8% to 10% of total project costs, and the project cost savings would have reduced design costs to between $11.6 million and $15.3 million, raising the question of whether DPW may have overcharged the project for project and construction management.

Design costs for the Earthquake Safety and Emergency Response (ESER) bond were $30.6 million (16.1%) of total project costs. Another Cumming’s audit report — again beyond the scope of the requested audit — opined the design costs should have been 8% to 10% of total project costs, and the project cost savings would have reduced design costs to between $11.6 million and $15.3 million, raising the question of whether DPW may have overcharged the project for project and construction management.Independent of Dratler, this author has to wonder why the Controller’s Office allowed DPW, as the auditee, to reduce the scope of the Cumming audit!

In addition, a Cumming’s PowerPoint presentation made to CGOBOC members noted that the ESER bond totaled $412.3 million, but that Cumming had only “reviewed” $248.6 million (60.3%) of the bond expenditures — and apparently Cumming’s didn’t review 39.7% of bond expenditures, significantly higher than Dratler’s observation Cumming hadn’t audited 25% of this bond.. This is all but an admission that Cumming didn’t audit the expenditures, it just “reviewed” them.

In addition, a Cumming’s PowerPoint presentation made to CGOBOC members noted that the ESER bond totaled $412.3 million, but that Cumming had only “reviewed” $248.6 million (60.3%) of the bond expenditures — and apparently Cumming’s didn’t review 39.7% of bond expenditures, significantly higher than Dratler’s observation Cumming hadn’t audited 25% of this bond.. This is all but an admission that Cumming didn’t audit the expenditures, it just “reviewed” them.

And particularly troubling is that voters had approved the ESER bond measure in June 2014 for just $400 million. How did it climb to $412.3 million by the time Cumming performed its “so-called audit”? Was the additional $12.3 million due to cost overruns? Were the cost overruns a direct result of change orders? What was the source of the additional $12.3 million in funding? And most importantly, did CGOBOC even bother investigating any of these clearly important questions?

CGOBOC should consider requesting and scheduling soon an independent outside audit to focus solely on DPW’s architecture and engineering fees since all general obligation bond funded projects incur project management, construction management, and design costs, and because Cumming’s construction audits have found DPW costs should be 50% lower than they are.

CGOBOC should consider requesting and scheduling soon an independent outside audit to focus solely on DPW’s architecture and engineering fees since all general obligation bond funded projects incur project management, construction management, and design costs, and because Cumming’s construction audits have found DPW costs should be 50% lower than they are. Changes in project scope should be managed through better reporting. The RRSS audit report disclosed there was an 8% reduction in the number of blocks of roadways repaved. Dratler asks how that project scope reduction was implemented. San Franciscans are entitled to scope reduction information, yet CGOBOC has not, to anyone’s knowledge, ever discussed openly how massive change orders have led directly to the reduction in scope of bond-funded projects.

Changes in project scope should be managed through better reporting. The RRSS audit report disclosed there was an 8% reduction in the number of blocks of roadways repaved. Dratler asks how that project scope reduction was implemented. San Franciscans are entitled to scope reduction information, yet CGOBOC has not, to anyone’s knowledge, ever discussed openly how massive change orders have led directly to the reduction in scope of bond-funded projects. It’s not known whether CGOBOC will consider and implement Dratler’s risk-based policy recommendations.

Elsewhere, Dratler has noted that many of the bond-funded soft costs are done by San Francisco’s Department of Building Inspection. For my part, I believe that many of the soft costs are also performed by the Department of Public Works. He shared in private correspondence that CGOBOC:

Should invest time reviewing final bond budgets early in a given bond’s lifecycle and when CGOBOC finds bonds with high soft costs at the outset, it should require an external audit to perform a detailed review of soft-cost budgets, since it is too late at the completion of a bond expenditure audit to do anything after learning that a given bond has high soft costs. Dratler’s concerns about examining pre-bond proposals, is also of reported concern to the City Controller’s Office.

Should invest time reviewing final bond budgets early in a given bond’s lifecycle and when CGOBOC finds bonds with high soft costs at the outset, it should require an external audit to perform a detailed review of soft-cost budgets, since it is too late at the completion of a bond expenditure audit to do anything after learning that a given bond has high soft costs. Dratler’s concerns about examining pre-bond proposals, is also of reported concern to the City Controller’s Office. Did not drill down after meeting materials showed the ESER bond expenditure was completed, but $100.2 million for the emergency response water system were not audited — at the request of DPW! How does DPW get to dictate which subprojects of a given bond will, or will not, be audited by the CSA There’s no information regarding whether that remaining 25% of the bond expenditures will be audited, or when.

Did not drill down after meeting materials showed the ESER bond expenditure was completed, but $100.2 million for the emergency response water system were not audited — at the request of DPW! How does DPW get to dictate which subprojects of a given bond will, or will not, be audited by the CSA There’s no information regarding whether that remaining 25% of the bond expenditures will be audited, or when.Dratler noted that none of the three bond expenditure audit reports performed and completed by Cumming’s presented any conclusions following a review of project change orders. Cumming’s was provided change order data for each of the three bonds, but the Cumming’s reports made no mention of change orders. That is an issue, Dratler maintains, that CGOBOC should address in all future external audits of bonds.

The External Audits of Bond Programs

There’s a paucity of external audits of bond programs. Dratler notes that the three Cumming external audits — of the ESER, RRSS, and SFGH rebuild bond measures — were approved by CGOBOC in 2015, but no new external audits were approved in 2016, or to date in 2017. What does that tell us? How can CGOBOC adequately fulfill its oversight-of-bonds expenditures mission, without independent, external audits?

There’s a paucity of external audits of bond programs. Dratler notes that the three Cumming external audits — of the ESER, RRSS, and SFGH rebuild bond measures — were approved by CGOBOC in 2015, but no new external audits were approved in 2016, or to date in 2017. What does that tell us? How can CGOBOC adequately fulfill its oversight-of-bonds expenditures mission, without independent, external audits?

City Controller Rosenfield stated during CGOBOC’s May 25 meeting that the audits CSA “self performs” (i.e., internal, not external, audits) are not “financial audits per se, but rather performance audits.” Clearly from the summary of the 233 CSA audits self performs that Dratler analyzed, Rosenfield was incorrect: The internal audits are neither financial audits, nor, for the most part, performance audits.

Rosenfield also noted that the paucity of the three external audits performed by Cumming’s have performed “transitional testing audits” comparing expense transactions against the bond authority. Rosenfield further claimed the external audits are “compliance checks, testing transactions ... payments made against the voter authorization. It’s a very narrow audit.”

Rosenfield also noted that the paucity of the three external audits performed by Cumming’s have performed “transitional testing audits” comparing expense transactions against the bond authority. Rosenfield further claimed the external audits are “compliance checks, testing transactions ... payments made against the voter authorization. It’s a very narrow audit.”

Elsewhere the Controller’s Office claims that the three Cumming audits to date have been “bond expenditure performance audits.” So which is it: “Transitional testing audits”? Or “performance audits”? Why can’t the Controller’s Office seem to keep its story straight?

Also during that May 25 CGOBOC meeting, Rosenfield observed that Cumming’s was chosen as an auditor for its experience in “construction management” rather than for its experience in “financial” CPA issues. How reassuring, or reasonable, is it that audits are performed by external auditors who do not have a financial background?

Again, after CGOBOC was created in 2002 and then was deemed to be the CARB in 2003, why did it take 13 years for CGOBOC to hire an outside firm to perform bond expenditure audits? Why did the City Controller/City Services Auditor allow this to happen?

Are City Hall and CGOBOC simply aiding and abetting rampant change order corruption?

Are City Hall and CGOBOC simply aiding and abetting rampant change order corruption?

Could this be dereliction of duty? Or might it be nonfeasance?

Monette-Shaw is a columnist for San Francisco’s Westside Observer newspaper, and a member of the California First Amendment Coalition (FAC) and the ACLU. Contact him at monette-shaw@westsideobserver.com.

Footnote:

1 Dratler is a former member of San Francisco’s 2014–2015 Civil Grand Jury that issued its report “Whistleblower Protection Ordinance Is In Need Of Change,” and a member of the 2012–2013 Civil Grand Jury that issued “Building a Better Future at the Department of Building Inspection,” (DBI) a damning report on the highly dysfunctional DBI, and also issued another Grand Jury 2012–2013 report: “Auditing the City Services Auditor: You Can Only Manage What You Measure.” Dratler clearly has experience — both from the perspectives of being a former Grand Jury member and a former member of CGOBOC — with the shortcomings of the City Controller’s City Services Auditor function.

A knowledgeable Certified Public Accountant, Dratler, now retired, spent most of his career as a financial executive working for large retailers. He was Vice President of Finance and Chief Accounting Officer for Williams Sonoma, a New York Stock Exchange-traded company. Dratler was subsequently appointed by the Grand Jury to serve on CGOBOC, and continues attending CGOBOC meetings as a member of the public. He’s one sharp cookie!