Printer-friendly PDF file

Printer-friendly PDF file

July 31, 2023

Part 2 of Two-Part Series

Costs to Rescue Laguna Honda Hospital Inch Up. Again.

LHH's Mismanagement Costs Reaches $64.9 Million

Complying With CMS Regulations Could Avoid Costs.

LHH Managers Chose Non-Compliance, Instead.

Were We Blackmailed Into Using Public Funds for Lobbyists?

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

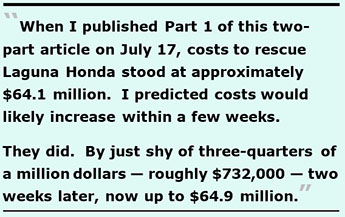

When Part 1 of this two-part article was published in the Westside Observer on July 17, costs to rescue Laguna Honda Hospital stood at approximately $64.1 million. I predicted they would likely increase within a few weeks.

They did. By just shy of three-quarters of a million dollars — roughly $732,000 — two weeks later, now up to $64.9 million.

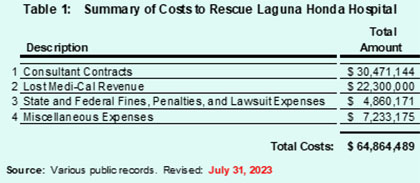

I had indicated Part 2 of this article would explore the State and Federal fines, penalties, and lawsuit expenses, plus additional miscellaneous expenses, that then subtotaled approximately $11.4 million not discussed in Part 1. In the past 12 days, public records show the additional expenses climbed by $731,685 — to a revised subtotal of $12 million.

I had indicated Part 2 of this article would explore the State and Federal fines, penalties, and lawsuit expenses, plus additional miscellaneous expenses, that then subtotaled approximately $11.4 million not discussed in Part 1. In the past 12 days, public records show the additional expenses climbed by $731,685 — to a revised subtotal of $12 million.

So, the total known costs to rescue LHH now stands at a revised total just shy of $64.9 million ($64,864,489) to date, as shown in the updated Table 1, below.

[Note: The additional two tables in Part 2 of this aerticle continue the numbering of tables in Part 1.]

Sadly, there has been zero accountability for LHH employees who caused these expenses, particularly no consequences for LHH’s senior management team who were directly, and mostly, responsible. Many of the expenses were completely avoidable, as the Health Commission and San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors surely must know.

Sadly, there has been zero accountability for LHH employees who caused these expenses, particularly no consequences for LHH’s senior management team who were directly, and mostly, responsible. Many of the expenses were completely avoidable, as the Health Commission and San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors surely must know.

Costs are projected to climb some more, perhaps by another $1 million before September 1. Here’s Part 2 of this article.

Fines, Penalties, and Lawsuit Expenses

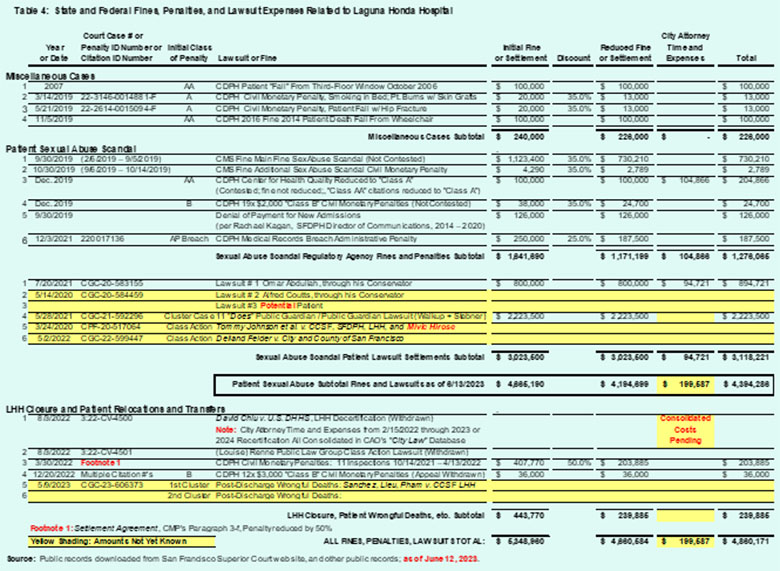

To date, we know of at least $4.9 million in various expenses related to fines, penalties, and lawsuits involving Laguna Honda Hospital’s mismanagement over the years, as shown in Table 4.

After all, had LHH’s managers simply remained in compliance with CMS’ nursing home regulations they could have avoided all $5 million of the fines, penalties, and lawsuit expenses. They deliberately chose non-compliance, instead.

After all, had LHH’s managers simply remained in compliance with CMS’ nursing home regulations they could have avoided all $5 million of the fines, penalties, and lawsuit expenses. They deliberately chose non-compliance, instead.

Of note, the yellow shading shown in Table 4 highlighting currently unknown costs portends that these lawsuit expenses will climb significantly during the coming months, in part because:

The City Attorney’s time and expenses fighting the $2.2 million settlement awarded in the Public Guardian / Public Guardian lawsuit (case # CGC-21-592296) has not yet been released, but it’s known the CAO fought that case vigorously and spent significant time trying to derail the case.

The City Attorney’s time and expenses fighting the $2.2 million settlement awarded in the Public Guardian / Public Guardian lawsuit (case # CGC-21-592296) has not yet been released, but it’s known the CAO fought that case vigorously and spent significant time trying to derail the case.  Eventually, the CAO filed a lawsuit on LHH’s behalf in the United States District Court – Northern District of California on August 3, 2022 — formally moving from just “Dispute Resolution” and “Departmental Appeals” administrative steps to a formal lawsuit challenging LHH’s decertification. The lawsuit was assigned as Case Number 3:22-CV-4500.

Eventually, the CAO filed a lawsuit on LHH’s behalf in the United States District Court – Northern District of California on August 3, 2022 — formally moving from just “Dispute Resolution” and “Departmental Appeals” administrative steps to a formal lawsuit challenging LHH’s decertification. The lawsuit was assigned as Case Number 3:22-CV-4500. The CAO has combined all of the administrative proceedings — starting with the “Informal Dispute Resolution” phase, to the consolidated “Appeals” docket, plus the formal lawsuit and the “LHH Settlement Agreement” — under the protective umbrella of Case Number 3:22-CV-4500. Now, the CAO refuses to release details of the costs of City Attorney time and expenses for each of these distinct procedural steps, and claims it won’t release any of these costs until it closes out Case Number 3:22-CV-4500. The CAO has refused to disclose any of those time and expense amounts since December 2021 that are captured in its CityLaw database that records each City attorney’s time spent on each case number, on the theory that releasing the City Attorney’s expenses might jeopardize its litigation strategy by sharing that data with opposing Counsel, who might somehow develop an unfair advantage by knowing those expenses during litigation.

The CAO has combined all of the administrative proceedings — starting with the “Informal Dispute Resolution” phase, to the consolidated “Appeals” docket, plus the formal lawsuit and the “LHH Settlement Agreement” — under the protective umbrella of Case Number 3:22-CV-4500. Now, the CAO refuses to release details of the costs of City Attorney time and expenses for each of these distinct procedural steps, and claims it won’t release any of these costs until it closes out Case Number 3:22-CV-4500. The CAO has refused to disclose any of those time and expense amounts since December 2021 that are captured in its CityLaw database that records each City attorney’s time spent on each case number, on the theory that releasing the City Attorney’s expenses might jeopardize its litigation strategy by sharing that data with opposing Counsel, who might somehow develop an unfair advantage by knowing those expenses during litigation. The public will not learn any details of the combined costs of the CAO’s time and expenses until many months after LHH gains re-admission to the Medicare reimbursement program, is fully recertified (assuming it eventually will be), and resumes admitting patients — which appears will probably not happen by the end of December 2023.

The public will not learn any details of the combined costs of the CAO’s time and expenses until many months after LHH gains re-admission to the Medicare reimbursement program, is fully recertified (assuming it eventually will be), and resumes admitting patients — which appears will probably not happen by the end of December 2023.Before it’s all over, the fines, penalties, and lawsuit expenses shown in Table 4 will probably climb from this preliminary $5 million to between $10 million and $15 million — if not substantially more. Again, had LHH simply remained in compliance with CMS’ regulations, these expenses dating back to 2019 could have been completely avoided.

Miscellaneous Expenses

Miscellaneous Expenses

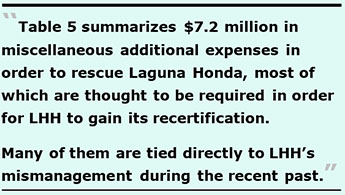

Table 5 summarizes at least $7.2 million in miscellaneous additional expenses in order to rescue Laguna Honda, most of which are thought to be required in order for LHH to gain its CMS recertification. Many of them are tied directly to LHH’s mismanagement during the recent past.

Some of the expenses are based on estimates extrapolated from public records.

Row 1 of Table 5 involves an LHH budget “Program Change Tequest” submission document that revealed LHH is adding another 15 full-time equivalent staff employees (and deleting one full-time equivalent employee), for a net gain of 14 job classification code positions at an increased cost of $2.5 million annually going forward, including fringe benefits.

Row 1 of Table 5 involves an LHH budget “Program Change Tequest” submission document that revealed LHH is adding another 15 full-time equivalent staff employees (and deleting one full-time equivalent employee), for a net gain of 14 job classification code positions at an increased cost of $2.5 million annually going forward, including fringe benefits. It is thought LHH’s “Kitchen Floor Replacement Project,” which has been identified as a Capital Improvement project, is likely to cost several million dollars. It should actually have been repaired and replaced long before now. The floor needed to be replaced because a cart-wash area for heavy food carts had been poorly designed by the building’s architects in 2008 using glass in the floor tiles’ design. Shortly after the hospital opened in June 2010 the flooring severely cracked and then didn’t drain properly, which lead to an ongoing problem causing mold in the kitchen.

It is thought LHH’s “Kitchen Floor Replacement Project,” which has been identified as a Capital Improvement project, is likely to cost several million dollars. It should actually have been repaired and replaced long before now. The floor needed to be replaced because a cart-wash area for heavy food carts had been poorly designed by the building’s architects in 2008 using glass in the floor tiles’ design. Shortly after the hospital opened in June 2010 the flooring severely cracked and then didn’t drain properly, which lead to an ongoing problem causing mold in the kitchen.  If anything, Line 9 in Table 5 to use additional new Capital Improvement Funds to replace LHH’s kitchen floor is particularly outrageous because the $15.3 million the City received from settlement of the Stantec lawsuit in 2014 was deposited into the City’s General fund, not used to immediately repair LHH’s kitchen floor. Alternatively, since Stantec was not released from any further lawsuits and liability from “latent defects,” LHH’s defective kitchen floor should have been repaired long before now using a “latent defect” funding source, and not need taxpayers footing the bill using more scarce Capital Improvement Funds.

If anything, Line 9 in Table 5 to use additional new Capital Improvement Funds to replace LHH’s kitchen floor is particularly outrageous because the $15.3 million the City received from settlement of the Stantec lawsuit in 2014 was deposited into the City’s General fund, not used to immediately repair LHH’s kitchen floor. Alternatively, since Stantec was not released from any further lawsuits and liability from “latent defects,” LHH’s defective kitchen floor should have been repaired long before now using a “latent defect” funding source, and not need taxpayers footing the bill using more scarce Capital Improvement Funds. LHH suddenly reported on July11 that in order to reduce the use of patient “restraints” during the previous six months, LHH had begun “partnering with every resident to have their bed exchanged with an ‘equivalent’ bed.” Many LHH patients and their families were reluctant to do so because the project involved eliminating the use of all bed siderails that patients were accustomed to, to prevent injuries from falling out of their beds. But in an effort to reduce the potential of injuries from patient entrapment in the siderails, LHH was adamant the bed rails be removed and alternative mobility devices such as trapezes be installed to assist patients getting in and out of their beds safely.

LHH suddenly reported on July11 that in order to reduce the use of patient “restraints” during the previous six months, LHH had begun “partnering with every resident to have their bed exchanged with an ‘equivalent’ bed.” Many LHH patients and their families were reluctant to do so because the project involved eliminating the use of all bed siderails that patients were accustomed to, to prevent injuries from falling out of their beds. But in an effort to reduce the potential of injuries from patient entrapment in the siderails, LHH was adamant the bed rails be removed and alternative mobility devices such as trapezes be installed to assist patients getting in and out of their beds safely.The $7.2 million to date in LHH’s “miscellaneous” recertification-related expenses shown in Table 5 will climb even higher.

LHH Staffing Increases

As LHH prepares to submit its application for CMS certification, it’s clear LHH isn’t significantly increasing its direct patient care staffing, despite the addition of 21 new positions shown on Rows 1 and 2 in Table 5 above, and the shuffling around of four additional positions.

That’s in part because San Francisco’s new “Annual Salary Ordinance” (ASO) for the Fiscal Year that began on July 1, 2023 for the next two-year budget through June 30, 2025 — finally passed by our Board of Supervisors on July 25 — does not show a significant difference in LHH’s budgeted and authorized “Full-Time Equivalent” (FTE) positions by job classification code numbers, compared to the previous ASO for the Fiscal Year that ended on June 30, 2023.

The new two-year ASO just adopted authorizes 1,503.92 FTE’s starting on July 1, 2023 compared to the previous ASO for the period ending on June 30, 2023, which had authorized a total of 1,482.90 FTE’s. That represents an increase of just 21.02 additional FTE’s between June 30 and July 1, 2023. Then on July 1, 2024, LHH will add another 3.85 FTE’s, pushing the total FTE’s added during the two-year budget cycle to a total of 24.87 additional FTE’s.

Of those additional 24.87 FTE positions, there will be a total increase of just 7.1 FTE Nursing positions that provide direct patient care. Again, adding just seven Nursing positions is also unlikely to substantially improve substandard patient care.

Of those additional 24.87 FTE positions, there will be a total increase of just 7.1 FTE Nursing positions that provide direct patient care. Again, adding just seven Nursing positions is also unlikely to substantially improve substandard patient care.

FTE staffing levels of CNA’s, PCA’s, and HHA’s will all remain flat (unchanged)) between the two ASO’s across Fiscal Years. There will be an increase of 3.1 FTE RN’s and an increase of 4.0 FTE LVN’s, despite neither increase having been requested in the “program change request” submitted to SFDPH and then forwarded to the Mayor’s Budget Director.

Given that between the additional 14 FTE positions included in the “program change request” plus the 6.0 FTE positions for Stationary Engineers total 20 of the additional 24.87 FTE’s approved in the ASO, it’s unclear how LHH managed to juggle adding 7.1 Nursing FTE’s that provide direct patient care.

Weirdly, LHH’s monthly “Vacancy Reports by FTE” presented to the Health’s Commission’s LHH-JCC — a Joint Conference Committee consisting of three Health Commissions and senior management of Laguna Honda — reported that LHH had a total of 1,430.1 FTE’s in August 2022, and 1,454.6 FTE’s in January 2013, even though the ASO had authorized LHH to have 1,482.90 FTE’s during the entire Fiscal Year 2022–2023.

Weirdly, LHH’s monthly “Vacancy Reports by FTE” presented to the Health’s Commission’s LHH-JCC — a Joint Conference Committee consisting of three Health Commissions and senior management of Laguna Honda — reported that LHH had a total of 1,430.1 FTE’s in August 2022, and 1,454.6 FTE’s in January 2013, even though the ASO had authorized LHH to have 1,482.90 FTE’s during the entire Fiscal Year 2022–2023.

Why the “Vacancy Reports by FTE” had reported LHH had 52.8 and 28.3 fewer FTE’s, respectively, in those two monthly reports than the FTE’s authorized in the ASO isn’t known. And it’s not known why the monthly reports don’t consistently report a single authorized FTE headcount every month.

A future article may explore the massive increase in the sheer number of Directors of Nursing, separate Nursing Directors, and Nursing Manager positions that have evolved on LHH’s published Organization Charts between March 2022 (after LHH was decertified in April 2021) and LHH’s proposed “pilot” Nursing re-organization chart LHH’s acting CEO, Roland Pickens announced on June 2022, followed by LHH’s most recent organization chart released on July 25, 2023, which has grown extremely complex.

An extract of just the Nursing “leadership” team on the July 25 organization chart shows a potentially highly bloated, top-heavy Nursing hierarchy that has evolved in just the past year as LHH has struggled to prepare for its recertification application. The extract shows at least 62 positions (by incumbents’ names, job classification codes, and organizational functions) in LHH’s Nursing management structure.

The organization chart still appears to be in rapid flux. A June 23, 2023 version of it presented to the Health Commission had contained a “box” labeled as “RN’s – 3 FTE’s” as reporting to an “Infection Control Nurse Manager” (perhaps Keith Howard). The July 25 organization chart, however, removed Mr. Howard’s name and removed the box for the three RN’s reporting to the “Infection Control Nurse Manager.” The chart now lists the “Infection Control Nurse Manager” position as being vacant.

The organization chart still appears to be in rapid flux. A June 23, 2023 version of it presented to the Health Commission had contained a “box” labeled as “RN’s – 3 FTE’s” as reporting to an “Infection Control Nurse Manager” (perhaps Keith Howard). The July 25 organization chart, however, removed Mr. Howard’s name and removed the box for the three RN’s reporting to the “Infection Control Nurse Manager.” The chart now lists the “Infection Control Nurse Manager” position as being vacant.

CMS began requiring Skilled Nursing Facilities to have at least a part-time “Infection Preventionist” beginning on November 28, 2019. But California has stronger standards, and began requiring skilled nursing to have a full-time, dedicated “Infection Preventionists” on January 1, 2021 who must be a Registered Nurse or a Licensed Vocational Nurse. Unfortunately, LHH’s recent iterations of its organization chart does not show any boxes listing a functional area of responsibility labeled as an Infection Preventionist displaying the name of an incumbent.

The July updated chart also added a “Nursing Director Restraints Co-Lead” — ostensibly for the “Restraints Reduction” initiative — that had not been included on the June 23 version. Why LHH needed to assign a Job Classification Code 2324, “Nursing Supervisor” to lead this effort isn’t known. The 2324 Nursing Supervisor job classification can earn salaries of up to $10,728 bi-weekly, which translates to $368,743 between salary and fringe benefits annually.

Of concern, while CMS began requiring all skilled nursing facilities to have an “Infection Preventionist” as far back as 2019, it’s worrisome LHH’s org chart updated in July doesn’t display one. That’s because, in part, as recently as its third “90-Day Monitoring Survey” inspection in June 2023, LHH continued receiving F-Tag F880 deficiencies involving “Infection Prevention and Control.”

A Final Word

A Final Word

Costs included in this two-part series article do not include expenses over the past 13 years of LHH having been reduced from its planned 1,200-bed rebuild to just 780 beds in 2010. The 420 beds eliminated from the replacement project — reportedly initially suggested as a cost-cutting measure by the architects and Turner Consulting — has resulted in the City having to place Medi-Cal patients who are conserved by the City into far away, out-of-county skilled nursing facilities. That has had a direct cost to the City, and untold costs in human suffering to San Franciscans dumped out of county away from their families, friends, and support networks.

It’s not known yet how much further the now $64.9 million in escalating costs will rise. It will probably easily reach $80 million or more, with zero accountability for LHH’s former and current managers whose mismanagement caused LHH’s decertification.

Monette-Shaw is a columnist for San Francisco’s Westside Observer newspaper, and a retired City employee. He received a James Madison Freedom of Information Award in the “Advocacy” category from the Society of Professional Journalists–Northern California Chapter in 2012. He’s a member of the California First Amendment Coalition (FAC) and the ACLU. Contact him at monette-shaw@westsideobserver.com.