Westside Observer

Westside Observer June 2015 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Secret City Attorney Opinion Overturns Prop Q

Detrimental Skilled Nursing Facility Cuts

Article in Press Printer-friendly PDF file

Westside Observer

Westside Observer

June 2015 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Secret

City Attorney Opinion Overturns Prop Q

Detrimental

Skilled Nursing Facility Cuts

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

Imagine for a moment being admitted to a local private hospital — say St. Mary’s — suffering from a stroke, brain injury, or heart attack. As you’re recovering from your acute-care medical event, imagine you’re told that you need 12-day, short-term skilled nursing care to re-learn how to feed, groom, and dress yourself, and to re-learn how to walk safely without falling.

Then imagine being informed by the private hospital you were admitted to that it is discharging you post-acute care because it has no hospital-based skilled nursing beds to help transition you back to being independent and functioning.

Finally, imagine being told the hospital is dumping you into a short- or long-term skilled nursing facility out-of-county because there are no skilled nursing beds in San Francisco to provide you with short- or long-term rehabilitation in a post-acute care setting.

You

might find yourself wondering how such a scenario developed in

the City of St. Francis, disguised by Health Commission claims

that under so-called “reforms” in the Affordable Care

Act, it may be permissible for San Francisco hospitals to make

cuts in providing healthcare services, even if detrimental, by

misinterpreting language required by a City Ordinance, based on

an Orwellian secret City Attorney opinion.

You

might find yourself wondering how such a scenario developed in

the City of St. Francis, disguised by Health Commission claims

that under so-called “reforms” in the Affordable Care

Act, it may be permissible for San Francisco hospitals to make

cuts in providing healthcare services, even if detrimental, by

misinterpreting language required by a City Ordinance, based on

an Orwellian secret City Attorney opinion.

Voters Spoke in 1988

In November 1988 — nearly 30 years ago — San Franciscans were so concerned about private-sector hospital mergers that were eliminating needed medical services suddenly, without advance notice and without community input, that 16,900 citizen petition signatures qualified “Proposition Q,” the Health Care Community Service Planning Ordinance, for the ballot, which passed with a resounding 129,257 votes in support — 59.8% of ballots cast.

“Proposition Q” provided that before private hospitals or clinics can eliminate or reduce any healthcare services, they are required to notify San Francisco’s Public Health Commission at least 90 days in advance, and the Health Commission, in turn, is then required to hold two public hearings to evaluate and decide whether the proposed service reductions will or will not have a detrimental impact on provision of healthcare services in the community.

The official argument

in favor of Proposition Q in the 1988 voter guide was authored

by Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi, then State Assemblymen Willie L.

Brown and John Burton, and then Board of Supervisors President

Nancy Walker and then Supervisor Harry Britt. The five legislators

must have known how dearly San Franciscans held Prop Q to their

hearts.

The official argument

in favor of Proposition Q in the 1988 voter guide was authored

by Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi, then State Assemblymen Willie L.

Brown and John Burton, and then Board of Supervisors President

Nancy Walker and then Supervisor Harry Britt. The five legislators

must have known how dearly San Franciscans held Prop Q to their

hearts.

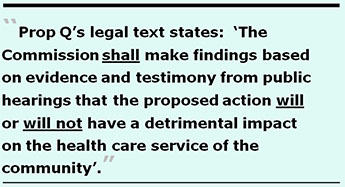

The legal text in the 1988 voter guide states in relevant part: “The [Health] Commission shall make findings based on evidence and testimony from public hearings that the proposed action will or will not have a detrimental impact on the health care service of the community” [emphasis added]. The legal text unequivocally mandates the Health Commission shall make an up or down ruling on whether reduction or elimination of health care services will or will not have detrimental effects. There’s no missing the duties Prop Q imposed on Health Commissioners.

Negligent Public health Commission?

Although an April 29, 2015 Department of Public Health (DPH) memo summarizing projections shows on page 5 that hospital-based skilled nursing facility (SNF) beds (beds affiliated with and operated by private-sector hospitals, as opposed to community-based free-standing SNF units) will have declined from 2,166 beds in 2002 to just 1,240 beds in 2020 — a whopping 42.8% decline and loss of 926 hospital-based SNF beds — the four Prop Q hearings held since 1988 (see below) document that the Health Commission has apparently only held hearings on the closure or reduction on a total of 90 of the 926 hospital-based SNF beds lost since 2002.

This begs the question:

Did the Health Commission allow the loss of the other 836 hospital-based

SNF beds — including the 420 skilled nursing beds eliminated

from the Laguna Honda Hospital rebuild that opened in 2010 —

between 2002 and 2020 without Prop Q hearings? How did San Francisco

lose 43% of its hospital-based SNF beds without adequate Health

Commission Prop Q oversight hearings? Isn’t that negligence?

This begs the question:

Did the Health Commission allow the loss of the other 836 hospital-based

SNF beds — including the 420 skilled nursing beds eliminated

from the Laguna Honda Hospital rebuild that opened in 2010 —

between 2002 and 2020 without Prop Q hearings? How did San Francisco

lose 43% of its hospital-based SNF beds without adequate Health

Commission Prop Q oversight hearings? Isn’t that negligence?

According to the Health Commission’s Executive Secretary, the Commission appears to have only held four Prop Q hearings during the past 13 years since 2002. It’s not known how many Prop Q hearings the Commission may have held in the 14 years between 1988 and 2002, if any.

The Commission held its first Prop Q hearing on April 4, 1995; Resolution 10-95 that it adopted claimed the outsourcing of various post-acute care services from CPMC to an outfit called the Guardian Foundation would not have a detrimental effect on healthcare services to San Franciscans. The Resolution asserted that the Guardian Foundation would “expand availability of post-acute care services to the San Francisco community and would ensure the continuation of the quality continuum of care to patients.” The Resolution noted the Guardian Foundation would manage CPMC’s skilled nursing unit on its California Street campus, with CMPC continuing to own the unit.

The second Prop Q hearing was held by the Health Commission November 13, 2007 to consider the elimination of St. Francis Memorial Hospital’s 34-bed skilled nursing unit; Resolution 14-07 the Commission adopted determined the closure of St. Francis’ skilled nursing beds would have a detrimental impact.

A third Prop Q hearing

was held on July 15, 2014, again regarding CMPC’s plan to

consider eliminating 24 staffed skilled nursing beds, from 99

staffed to just 75 staffed beds. This was particularly egregious,

considering the fact that at the time CPMC was licensed to operate

212 skilled nursing beds, but had chosen — like many hospital-based

skilled nursing units do — to operate and staff only a fraction

(46.7%) of the beds they are licensed to have. Resolution 14-08 that the Commission adopted

determined the closure of CPMC’s skilled nursing beds would

have a detrimental impact.

A third Prop Q hearing

was held on July 15, 2014, again regarding CMPC’s plan to

consider eliminating 24 staffed skilled nursing beds, from 99

staffed to just 75 staffed beds. This was particularly egregious,

considering the fact that at the time CPMC was licensed to operate

212 skilled nursing beds, but had chosen — like many hospital-based

skilled nursing units do — to operate and staff only a fraction

(46.7%) of the beds they are licensed to have. Resolution 14-08 that the Commission adopted

determined the closure of CPMC’s skilled nursing beds would

have a detrimental impact.

[Editor: Note that the 2014 Resolution switched from listing the resolution number adopted in any given year first followed by the year in which adopted, to listing the year adopted first.]

Crying Poor, St. Mary’s Proposes Shuttering Its SNF

Less than a year

after the Commission ruled last July that CPMC’s closure

would have a detrimental effect, a second draft Resolution dated May 14 debated on May

19, 2015 indicated the Health Commission would consider during

its fourth Prop Q hearing a proposal by St. Mary’s Hospital

to close its 32-bed skilled nursing facility (SNF).

Less than a year

after the Commission ruled last July that CPMC’s closure

would have a detrimental effect, a second draft Resolution dated May 14 debated on May

19, 2015 indicated the Health Commission would consider during

its fourth Prop Q hearing a proposal by St. Mary’s Hospital

to close its 32-bed skilled nursing facility (SNF).

Health Commissioner David Singer cleverly asserted during the hearing St. Mary’s proposed SNF closure is a very legitimate financial issue under the Affordable Care Act, since St. Mary’s cited in its March 16, 2015 notice to the Health Commission that shifts in health care reimbursement to hospital-based programs, and prolonged and substantial financial losses operating its SNF, as the reason to seek its closure.

Singer had to have known that the San Francisco Business Times reported September 25, 2014 that Dignity Health — St. Mary’s parent company — had seen a nine percent increase to its profits in 2014 to $885 million on overall revenue of $10.7 billion. Dignity’s 2014 profits compared to “relatively measly” $135 million profits two years earlier in 2012.

Unfortunately, the

April 19 DPH analysis provided to the Health Commission noted

above providing background information for consideration of St.

Mary’s proposal, failed to clearly point out to Health Commissioners

that between 2013 and 2020, DPH projects an additional loss of

346 hospital-based SNF beds, to a total of just 1,240 by 2020.

Unfortunately, the

April 19 DPH analysis provided to the Health Commission noted

above providing background information for consideration of St.

Mary’s proposal, failed to clearly point out to Health Commissioners

that between 2013 and 2020, DPH projects an additional loss of

346 hospital-based SNF beds, to a total of just 1,240 by 2020.

In addition, the April 19, 2015 DPH projections memo noted that overall, the total number of SNF beds — including both hospital-based and freestanding SNF’s — declined 22%, from 3,540 in 2002, to just 2,758 in 2013. And that by 2020, there will only be a total of 2,371 SNF beds in San Francisco. DPH failed to clearly summarize for Health Commissioners that by 2020 there will have had an overall 33% loss of 1,169 SNF beds since 2002, including the 926 hospital-based, plus another 243 community-based freestanding, SNF beds.

That’s assuming there will be no further loss of hospital-based or freestanding SNF beds in San Francisco during the next four-and-a-half years between now and 2020.

This is after the Health Commission was informed in 2014 during the CMPC Prop Q hearing that San Francisco is facing at least a 700-bed shortage of skilled nursing beds within the next 30 years, an overall shortage that may now be significantly higher, since a May 2011 analysis prepared by Resource Development Associates that DPH had commissioned is now four years old and probably sadly out of date.

Interestingly, the

Commission’s May 5 meeting minutes indicate Health Commissioner David

Pating, MD (who is a psychiatrist and Chief of Addiction Medicine

at Kaiser San Francisco) stated he’s unsure if he agrees

with the DPH recommendation that closing St. Mary’s SNF will

be detrimental, because it only has seven patients with low average

lengths of stay in the SNF units. Commissioner Pating misses the

point: This is not just about closing seven beds. Closing its

SNF means St. Mary’s will undoubtedly relinquish its 32-bed

license. That’s a significant number, and a detrimental loss,

of licensed bed capacity.

Interestingly, the

Commission’s May 5 meeting minutes indicate Health Commissioner David

Pating, MD (who is a psychiatrist and Chief of Addiction Medicine

at Kaiser San Francisco) stated he’s unsure if he agrees

with the DPH recommendation that closing St. Mary’s SNF will

be detrimental, because it only has seven patients with low average

lengths of stay in the SNF units. Commissioner Pating misses the

point: This is not just about closing seven beds. Closing its

SNF means St. Mary’s will undoubtedly relinquish its 32-bed

license. That’s a significant number, and a detrimental loss,

of licensed bed capacity.

The May 5 meeting minutes also show on page 3, and the meeting’s audio recording reveals, that Ms. Patil, a Health Program Planner in DPH’s Office of Policy and Planning, stated data shows a quarter of community SNF patients in freestanding SNF’s are discharged by way of re-admission to hospitals. The minutes should have more closely matched the audio to indicate that “a quarter of patients discharged from community-based SNF settings are re-admitted to hospitals.” The minutes also didn’t report that Patil’s April 29 memo noted “the vast majority of discharges from freestanding SNF’s (85%) occur within 3 months or less of the resident’s admission.”

After all, if almost a quarter of SNF discharges are for hospital re-admissions and occur within three months of initial SNF admission, this suggests that either patients are being discharged too quickly from acute care settings to SNF’s in the first place, or that they are not receiving the proper level of care with adequate lengths of stay in hospital-based or community-based SNF settings, or discharge planners may be ignoring patients’ acuity level prior to admission to freestanding community-based SNF’s.

What About Out-of-County “Patient Dumping” Discharges?

Finally, on page 5 of the Health Commission’s May 5 minutes, Commissioner Chung asked whether discharges to out-of-county SNF’s are common due to a lack of SNF beds in San Francisco. The minutes show that St. Mary’s Ms. Yeant sidestepped a direct answer, saying out-of-county discharges are not ideal, failing to answer Commissioner Chung’s question about whether historical out-of-county discharge data show the practice to be common.

Commissioner Chung,

Commissioner Pating, and Commission President Edward Chow must

all know that SNF out-of-county discharge data could help inform

community-based post-acute care planning. The Health Commission

has an obligation to report transparently to San Franciscans just

how widespread SNF out-of-county discharges are, and what types

of out-of-county facilities patients are discharged to; San Franciscans

have every right to be told this data.

Commissioner Chung,

Commissioner Pating, and Commission President Edward Chow must

all know that SNF out-of-county discharge data could help inform

community-based post-acute care planning. The Health Commission

has an obligation to report transparently to San Franciscans just

how widespread SNF out-of-county discharges are, and what types

of out-of-county facilities patients are discharged to; San Franciscans

have every right to be told this data.

As I reported in “The Big Squeeze: Dys-Integration of ”Old Friends“ in the Westside Observer in July 2014, out-of-county discharge data is more than likely being collected by San Francisco’s Department of Public Health and San Francisco’s Department of Aging and Adult Services (DAAS) in a database called SF GetCare, that the two Departments have contracted with for development by RTZ Associates as far back as 2003, and have paid RTZ at least $5.6 million to develop 10 to 12 separate but interrelated component modules.

I know the SF GetCare database components more than likely share fields of data showing discharge location by type of facility and location, because SF GetCare was initially prototyped from a Microsoft Access database I assisted in developing in Laguna Honda Hospital’s Rehabilitation Services Department. As any first-year programmer — or a first-year doctor or nurse — knows, tracking the name of the facility a patient is discharged to and the facility’s location is not rocket science to capture; both are necessary data elements for post-discharge follow-up.

Supervisor David

Campos peppered Director of Public Health Barbara Garcia about

discharge location data during a hearing on March 20, 2014 to

learn whether patients are being “integrated” into San

Francisco communities. DPH has adamantly refused to provide historical

data on discharges to, or admission “diversions” to,

out-of-county facilities since 2003. It’s unknown why DPH

struggles so mightily to prevent release of aggregate discharge

data documenting how many San Franciscans are being dumped out

of county.

Supervisor David

Campos peppered Director of Public Health Barbara Garcia about

discharge location data during a hearing on March 20, 2014 to

learn whether patients are being “integrated” into San

Francisco communities. DPH has adamantly refused to provide historical

data on discharges to, or admission “diversions” to,

out-of-county facilities since 2003. It’s unknown why DPH

struggles so mightily to prevent release of aggregate discharge

data documenting how many San Franciscans are being dumped out

of county.

It’s suspected that the probable significant number of out-of-county discharges would be politically embarrassing to City officials from the Mayor on down, given implications about patient “dumping” during the same time as San Francisco’s current housing crisis and massive displacement of San Franciscans.

DPH and DAAS surely have this out-of-county discharge data, but simply don’t want to provide it. In fact, the Health Commission’s current vice-president, Commissioner Singer, formally requested out-of-county discharge data from DPH staff, but was rebuffed, given having received no response to his request for records.

Since Commissions

exist to provide oversight and direction to City departments,

observers believe that the failure of any department’s staff

to respond to any Commissioner is tantamount to obstruction, given

that various Boards and Commissions are charged with performing

due diligence, fiduciary oversight, and developing policies of

the Department a Commission governs. Failure to provide Commissioners

with data requested clearly interferes with any Commissioner’s

sworn duties to perform adequate oversight and ministerial duties.

Since Commissions

exist to provide oversight and direction to City departments,

observers believe that the failure of any department’s staff

to respond to any Commissioner is tantamount to obstruction, given

that various Boards and Commissions are charged with performing

due diligence, fiduciary oversight, and developing policies of

the Department a Commission governs. Failure to provide Commissioners

with data requested clearly interferes with any Commissioner’s

sworn duties to perform adequate oversight and ministerial duties.

For his part, Commissioner Singer needs to resubmit his request for the out-of-county discharge data to Director of Public Health Barbara Garcia, this time as an official’s public records request in his capacity as a Health Commissioner.

The State’s Long-Term Care Ombudsman, Benson Nadell, testified to Supervisor Campos on March 20, 2014:

Some observers believe that both short- and long-term care SNF beds are now being converted to sub-acute beds instead, under the guise of public-private partnerships, following an earlier era of converting long-term SNF beds to short-term or rehabilitation beds.

Detrimental

Impacts of SNF Bed Reductions

Detrimental

Impacts of SNF Bed Reductions

Ms. Patil’s April 29 memo to the Health Commission regarding St. Mary’s SNF closure proposal ends on a thud, although it acknowledges that an industry trend in converting long-term SNF beds to short-term SNF beds means that “any reduction of SNF beds, regardless of type, creates an overall capacity risk for San Francisco and is likely to have a detrimental impact.”

Patil’s April 29 memo notes, in fact, that “many seniors and persons with disabilities who require long-term care are forced to move outside the City … becoming socially and culturally isolated.”

During the first of its two hearings on May 5 regarding St. Mary’s proposal to close its SNF units, the Health Commission requested additional information on the short-term and long-term skilled nursing bed inventory in San Francisco.

In a follow-up May 13, 2015 memo to Health Commissioners prior to their second Prop Q hearing on closure of St. Mary’s SNF beds on May 19, Ms. Patil asserted that short-term beds are most often used for rehabilitation and recovery following acute-care hospital stays due to injury or illness, while long-term SNF beds are typically used by patients with chronic medical conditions, permanent disabilities on-going help with activities of daily living. Short-term stays are generally defined as being for three months or less, while long-term stays are defined as three months or longer.

DPH guessed at estimating

that the number of short-term vs. long-term SNF beds currently

available. Following its May 5 meeting, the Health Commission

requested additional data from Patil to stratify the number of

short-term and long-term beds in both freestanding and hospital

based SNF’s, data that Patil subsequently provided on May

13. But on May 19, Commissioner Chow quibbled over whether the

closure of 32 of approximately 180 hospital-based short-term SNF

beds was significant. The 32-bed SNF license at St. Mary’s

represents fully 17.8% of the 180 beds; as such it’s a significant

and detrimental cut of remaining hospital-based short-term beds.

DPH guessed at estimating

that the number of short-term vs. long-term SNF beds currently

available. Following its May 5 meeting, the Health Commission

requested additional data from Patil to stratify the number of

short-term and long-term beds in both freestanding and hospital

based SNF’s, data that Patil subsequently provided on May

13. But on May 19, Commissioner Chow quibbled over whether the

closure of 32 of approximately 180 hospital-based short-term SNF

beds was significant. The 32-bed SNF license at St. Mary’s

represents fully 17.8% of the 180 beds; as such it’s a significant

and detrimental cut of remaining hospital-based short-term beds.

St. Mary’s short-term SNF, by contrast, had average patient length of stay’s of just 12 days, and had an average of just six SNF patients daily during the past year, which apparently posed a great financial burden on the hospital.

Ms. Patil’s May 13 memo asserts that “the standard of care for post-acute services, such as skilled nursing care, has been moving from institutions [hospital-based facilities] to community-based skilled nursing and other support service alternatives.” Patil claims that as the Health Commission noted on May 5, eliminating hospital-based “institutional post-acute care options represents ’rational care,’ consistent with national trends.” It appears to many observers that the reduction of hospital-based post-acute care services is much more closer to “rationed care” than rational care.

Ms. Patil has acknowledged that there is a long wait list for long-term SNF beds in San Francisco. The Commission’s May 5 meeting minutes indicate she stated “as hospital-based short-term SNF beds close, this may impact the availability of long-term SNF beds for which there is already a long wait list in San Francisco and the Bay Area.”

Both Patil’s

May 13 memo to the Health Commissioners, and the Commission’s

second draft Resolution 15-08, assert that the reduction of hospital-based

SNF beds needs to be offset by increasing the availability of

community-based post-acute care alternatives to preserve and maintain

“capacity” to care for this patient population.

Both Patil’s

May 13 memo to the Health Commissioners, and the Commission’s

second draft Resolution 15-08, assert that the reduction of hospital-based

SNF beds needs to be offset by increasing the availability of

community-based post-acute care alternatives to preserve and maintain

“capacity” to care for this patient population.

Patil’s May 13 memo acknowledges that in order to maintain the overall capacity of post-acute care services, “rational reductions” in hospital-based beds needs to be “accompanied by corresponding increases in community-based care alternatives,” since San Francisco’s “community based skilled nursing resources are already stretched [thin] by existing capacity.” That’s because there has not been a concomitant 31.4% to 42.8% increase in community-based post-acute alternatives to replace hospital-based SNF beds that have been lost.

There has been little, to no, increase in community-based alternatives, at all.

Between St. Mary’s proposed SNF closure in 2015 and CMPC’s SNF closure in 2014, a detrimental loss of 56 hospital-based SNF beds is very significant over a one-year period, particularly since there has been zero corresponding increase in community-based capacity during the same time, a grim fact that cannot possibly have escaped notice of our Health Commissioners. To her credit, Ms. Patil reports that DPH believes reductions in hospital-based SNF care without a corresponding increase in community-based care alternatives places a burden on community systems — and for that reason alone, involves detrimental health care to San Franciscans.

Patil’s observations

appear to have been lost on our Health Commissioners, who unanimously

turned a deaf ear to the Health Department’s analyses indicating

St. Mary’s SNF closure will be detrimental.

Patil’s observations

appear to have been lost on our Health Commissioners, who unanimously

turned a deaf ear to the Health Department’s analyses indicating

St. Mary’s SNF closure will be detrimental.

Sabotaging the Will of Prop Q Voters

St. Mary’s so desperately wants a get-out-of-jail-free card, it appears that Health Commission president Edward Chow may be all too willing to assist in changing what is required of the Health Commission under Prop Q mandates.

Dr. Chow — appointed to the Health Commission in 1989 (shortly after Prop Q was passed in 1988) and reappointed seven times now, serving a total of 26 years on the Commission — has been involved in the dearth of Prop Q hearings conducted by the Health Commission since 2002, resulting in the loss of the 926 hospital-based SNF beds in just four Prop Q hearings during his tenure, including St. Mary’s hearing on May 19. Perhaps it’s time the good Dr. Chow be replaced with new blood on the Health Commission.

It is clear from

the Health Commission’s May 5 and May 19 hearings on St.

Mary’s SNF closure that DPH and the Health Commission are

desperately attempting to overturn the intent and will of Prop

Q voters, without having to ask those pesky voters to weigh in

again on whether Prop Q should now be changed, 27 years later.

It is clear from

the Health Commission’s May 5 and May 19 hearings on St.

Mary’s SNF closure that DPH and the Health Commission are

desperately attempting to overturn the intent and will of Prop

Q voters, without having to ask those pesky voters to weigh in

again on whether Prop Q should now be changed, 27 years later.

First, Director of Public Health Garcia stated at 1:03:45 on the Commission’s May 5 audio tape “Prop Q is from 1988 and it’s not where we are today.” How’s that for chutzpah?

Not to be outdone, Commissioner Chow stated at 1:06:02 on May 5:

Chow went on to ramble at 1:06:30 on May 5:

Although Patil had

noted in her oral presentation May 5 that St. Mary’s had

indicated in its March 16, 2015 notice to the Health Commission

that changes in healthcare reimbursement and on-going [financial]

losses of the SNF unit as reason for its closure, Abbie Yant,

St. Mary’s Vice President for Mission, Advocacy and Community

Health stated at 27:43 on videotape May 5:

Although Patil had

noted in her oral presentation May 5 that St. Mary’s had

indicated in its March 16, 2015 notice to the Health Commission

that changes in healthcare reimbursement and on-going [financial]

losses of the SNF unit as reason for its closure, Abbie Yant,

St. Mary’s Vice President for Mission, Advocacy and Community

Health stated at 27:43 on videotape May 5:

There you have it: Although the Health Commission was told St. Mary’s SNF unit closure was due to on-going financial losses, St. Mary’s Ms. Yant admitted that the hospital’s leadership unanimously decided to close the unit based on the hospital’s “values,” not necessarily for financial reasons.

Next, Health Commissioner Pating quibbled extensively about whether St. Mary’s closure would have a detrimental impact in the near term, or if the detrimental effect won’t happen until the long term. He was not convinced by DPH’s planning staff that there would be an immediate detrimental effect, but a day of reckoning might eventually arrive. Pating split hairs and ignored that once the beds and license are given up, there will be a detrimental effect sooner (in the short term, or right now) or later (in the long term, say ten years from now).

Commissioner Singer

also quibbled about whether DPH’s advice that St. Mary’s

closure would be detrimental and whether it might have an immediate

impact. Ms. Patil interjected, saying:

Commissioner Singer

also quibbled about whether DPH’s advice that St. Mary’s

closure would be detrimental and whether it might have an immediate

impact. Ms. Patil interjected, saying:

The Health Commission didn’t seem to understand DPH’s concern that shifting post-acute care hospital-based SNF care to short-term community SNF beds will have an immediate detrimental impact now, not ten years in the future.

Although the May 5 meeting minutes indicate President Chow encouraged the Commission to focus its discussion on the short-term impact on the post-acute care spectrum by closing St. Mary’s SNF unit, in fact Chow said “care,” not “impact.” The Health Commission’s secretary, Mark Morewitz, cleverly changed in the minutes Chow’s observation about how short-term care fits into the post-acute spectrum to being what kind of an impact it might have.

Similarly, the May 5 minutes assert that Chow stated “the City Attorney’s Office will need to be consulted” regarding addition of language to the Health Commission’s Resolution 15-08, and Chow suggested “the language of Proposition Q be reviewed to ascertain if it can be made more relevant and helpful.”

Morewitz appears

to have made this up when he prepared the minutes, since Chow

said nothing on the May 5 audiotape about contacting the City

Attorney for review of Prop Q, nor had Chow said anything on tape

about making Prop Q more “relevant and helpful.”

Morewitz appears

to have made this up when he prepared the minutes, since Chow

said nothing on the May 5 audiotape about contacting the City

Attorney for review of Prop Q, nor had Chow said anything on tape

about making Prop Q more “relevant and helpful.”

The May 5 meeting minutes mentioned neither Garcia’s claim Prop Q is from 1988 “and it’s not where we are today,” nor Chow’s claim Prop Q was from the 80’s. It’s clear Morewitz elided comments made during the hearing from the minutes, and also tossed into the minutes things that had not been said at all.

For her part, Health Commissioner Judith Karshmer blurted at 44:08 May 19 that she didn’t know the Prop Q law particularly well, and asked whether it has been the case that in past Prop Q hearings private-sector facilities have indicated that although they would be reducing or eliminating “something” [a given service], that they offer to offset it by replacing [lost SNF services] with “another thing” [an alternative service].

Thankfully, Director Garcia responded to Karshmer that hasn’t been the case in past Prop Q hearings. Garcia replied at 44:50:

City

Attorney Wades In

City

Attorney Wades In

Moving to the Commission’s May 19 second hearing on St. Mary’s, Commissioner Chow suddenly claimed — but had not mentioned on May 5 during the Commission’s first hearing on St. Mary’s proposal — that the City Attorney has apparently recently reviewed Prop Q. It’s not clear whether the City Attorney issued a formal written “opinion” on Prop Q between May 5 and May 19. Chow suggested the City Attorney review may allow the Health Commission to avoid ruling one way or another on whether reductions in services or closure of facilities will or will not have a detrimental effect. Chow said May 19 at 46:40 on audio:

Chow’s implication

of a fresh reading of language in Prop Q is ridiculous. The legal

text of Prop Q in the 1988 voter guide stated at the time that

the Commission “shall further explore in these public hearings

what alternative means are available in the community to provide

the service or services to be eliminated or curtailed.” It

didn’t need a new City Attorney “opinion” to uncover

the plain meaning of language in Prop Q that has existed for the

past 27 years. It appears Chow, Garcia and Karshmer may have simply

never bothered reading the legal text of Prop Q, or they would

have known they’ve had this new “tool” all these

years.

Chow’s implication

of a fresh reading of language in Prop Q is ridiculous. The legal

text of Prop Q in the 1988 voter guide stated at the time that

the Commission “shall further explore in these public hearings

what alternative means are available in the community to provide

the service or services to be eliminated or curtailed.” It

didn’t need a new City Attorney “opinion” to uncover

the plain meaning of language in Prop Q that has existed for the

past 27 years. It appears Chow, Garcia and Karshmer may have simply

never bothered reading the legal text of Prop Q, or they would

have known they’ve had this new “tool” all these

years.

Chow had a problem on his hands, since the agenda descriptions for May 5 and May 19, and the title of and body of the first two draft Resolutions, all stipulated that the Commission would rule on whether St. Mary’s SNF closure “will” or “will not” have a detrimental effect. Chow suggested May 19 that perhaps a creative way around the problem would be to change the wording in the title of the final Resolution adopted 19 to remove the “will” or “will not” phrase, as if by a stroke of the Health Commission’s pen it could unilaterally overturn the will of voters who passed Prop Q.

The five Commissioners

ignored the Elephant in the room: Having ruled in 2007 and 2014

the closure of a combined 58 hospital-based SNF beds between St.

Francis and CPMC would have a detrimental

impact, the Health Commission was about to waffle by taking no

position on whether closing St. Mary's 32-bed SNF would be detrimental.

The five Commissioners

ignored the Elephant in the room: Having ruled in 2007 and 2014

the closure of a combined 58 hospital-based SNF beds between St.

Francis and CPMC would have a detrimental

impact, the Health Commission was about to waffle by taking no

position on whether closing St. Mary's 32-bed SNF would be detrimental.

When Chow started to take a vote May 19 on whether to adopt changes to the final Resolution. Commissioner Singer thoughtfully interjected at 53:14, saying “The Resolution doesn’t have in the first sentence ’will or will not.’ Just to be clear for the record, you are proposing …”

Chow responded at 53:30, saying:

Again, Morewitz cleverly omitted multiple items from the minutes of the Commission’s May 19 meeting published and adopted on June 2. Most egregiously, Morewitz elided from the minutes Chow’s observation that the City Attorney had reportedly issued some sort of “advice,” or a formal written “opinion” interpreting Prop Q. The minutes failed to report clearly that the Commission would not be issuing a Finding on whether St. Mary’s closure will or will not be detrimental, or that Chow had indicated the Commission would issue a different Finding altogether.

The minutes omit that Chow wants to turn Prop Q hearings into “positive” hearings, and mentioned nothing about the Health Commission working with the Board of Supervisors to change Prop Q. The minutes omit that Chow suggested changing the title of the third draft of the Resolution would get around whether the Commission was making a Finding of “will or will not“ be detrimental.

At 54:21, Chow repeated:

“And once again I will reemphasize that the City Attorney

has indicated that we have discretion [regarding language in the

Resolution].” Morewitz cleverly substituted in the minutes

that the Commission has “latitude beyond” determining

whether service closures are detrimental or not, but the videotape

and audiotape contain no mention of this; Mark substituted “latitude”

for Chow’s claim of “discretion,” which mean different

things.

At 54:21, Chow repeated:

“And once again I will reemphasize that the City Attorney

has indicated that we have discretion [regarding language in the

Resolution].” Morewitz cleverly substituted in the minutes

that the Commission has “latitude beyond” determining

whether service closures are detrimental or not, but the videotape

and audiotape contain no mention of this; Mark substituted “latitude”

for Chow’s claim of “discretion,” which mean different

things.

And the minutes say nothing about the second and third Resolved clauses the Commission adopted, and fails to report that the finally Commission imposed in writing a six-month deadline for DPH to provide the Commission with SNF needs analyses.

Brazenly, Chow changed things up twice. Rather than ruling on whether a reduction in services will or will not be detrimental, he changed it up to being that the lack of post-acute care services in the community is the real culprit, blaming the lack of community-based alternatives rather than blaming St. Mary’s for eliminating its SNF beds.

Chow changed it up

a second time by saying that the Health Commission would be reaching

a different finding (not the “Finding” required by the

legal text of Prop Q and the Finding advertised on the two agendas,

the two draft resolution titles, and in the body of the two resolutions

debated on May 5 and May 19).

Chow changed it up

a second time by saying that the Health Commission would be reaching

a different finding (not the “Finding” required by the

legal text of Prop Q and the Finding advertised on the two agendas,

the two draft resolution titles, and in the body of the two resolutions

debated on May 5 and May 19).

It bears repeating that the obvious problem with this is that

the legal text of Prop Q that appeared in the voter guide to inform

citizens on what they were voting on specifically stated “the

Commission shall make findings that the proposed

action will or will not have a detrimental impact on healthcare

services in the community.” The legal text of Prop Q did

not provide that the

Health Commission could simply make other kinds of “findings”;

it provided that the Commission had to reach a single finding

of whether proposed actions “will” or “will not”

be detrimental.

And the actual question put to voters on the ballot forms specifically

said “… shall the Health Commission be required

to decide whether the change will impair health care services?

… [emphasis added]”

Health

Commission Unanimously Passes Final Resolution on St. Mary’s

Health

Commission Unanimously Passes Final Resolution on St. Mary’s

Predictably, a records request placed May 20 for the final Resolution adopted by the Health Commission revealed that Dr. Chow did, in fact, creatively edit the title of the Resolution striking out the “will or will not” clause, and the body of the Resolution also removed an up or down vote on whether St. Mary’s SNF closure would be detrimental.

Beginning around 32:13 on the May 19 video, Dr. Chow indicated a first “Resolved” statement would be changed to say “The closure of short-term skilled nursing facility beds without ensuring an appropriate level of post-acute care is available may result in unmet short-term skilled nursing needs of the community [emphasis added].”

Leading up to the May 19 Health Commission meeting, the second draft of the Resolution dated as late as May 14 and distributed with the agenda had included just two Resolved statements, the first of which indicated the Commissioners were considering an up or down vote on whether St. Mary’s SNF closure would or would not have a detrimental effect. The “will or will not” Finding was simply completely deleted from the final Resolution adopted, with no separate Health Commission vote taken on whether to do so.

Commissioner Singer proposed a friendly amendment designed to tone down whether there would be unmet skilled nursing needs; he proposed moving the “unmet” clause to the end. The first Resolved passed ended up reading “The closure of short-term skilled nursing facility beds without ensuring an appropriate level of post-acute care is available may result in short-term skilled nursing needs of the community not being met.”

A “Whereas” clause in the Resolution adopted indicates that “while institutional [hospital-based] post-acute care continues to decrease, the availability of community-based post-acute care will need to rise to maintain the capacity to care for San Francisco’s population.” There’s been no such increase in capacity.

Chow indicated at 33:13 a new second Resolved would read:

The second Resolved had not existed in the second draft of the Resolution dated May 14; between May 14 and May 19 it appears to have been hastily added. Chow further explained at 35:11:

This is clearly a

long-overdue admission that for fully eight years, the Department

of Public Health failed to conduct an analysis of short-term SNF

needs in coordination with other City agencies as the Commission

had requested in 2007. And sadly, the second Resolved statement

merely “encourages” DPH to finally get around to conducting

this study. It’s shameful this had to be added to St. Mary’s

Resolution in writing to spur DPH to comply with the Commission’s

2007 request, as if the word “encourages” will actually

result in action.

This is clearly a

long-overdue admission that for fully eight years, the Department

of Public Health failed to conduct an analysis of short-term SNF

needs in coordination with other City agencies as the Commission

had requested in 2007. And sadly, the second Resolved statement

merely “encourages” DPH to finally get around to conducting

this study. It’s shameful this had to be added to St. Mary’s

Resolution in writing to spur DPH to comply with the Commission’s

2007 request, as if the word “encourages” will actually

result in action.

The third Resolved statement adopted unchanged from the second draft of the Resolution, also merely “encourages” St. Mary’s to explore community benefit investments in other community-based post-acute care alternatives. There’s that toothless word “encourages” again, which likely carries no weight in law.

Interestingly, in response to a second records request also placed on May 20 for any written City Attorney “opinion” regarding interpretation for the Health Commission regarding Prop Q, the Health Commission’s secretary responded on May 29 (two working days before the Commission’s June 2 meeting) saying that to the extent the Health Commission has any responsive records, advice and opinions from the City Attorney are protected by attorney-client communications, and/or attorney work product privileges, and won’t be provided to members of the public.

In one fell swoop,

Chow — apparently with the City Attorney Office’s help

— simply changed the Prop Q hearing into some other sort

of hearing, without approval by the voters who have not given

Chow, the Health Commission, or the City Attorney license to thwart

their will by thwarting Prop Q.

In one fell swoop,

Chow — apparently with the City Attorney Office’s help

— simply changed the Prop Q hearing into some other sort

of hearing, without approval by the voters who have not given

Chow, the Health Commission, or the City Attorney license to thwart

their will by thwarting Prop Q.

/City Attorney Makes George Orwell Proud

Not only does our City Attorney illegally advise City Departments on how to evade complying with the Sunshine Ordinance (which City Attorney advice is explicitly prohibited by our local Sunshine ordinance), the St. Mary’s Prop Q hearing offers proof that our City Attorney apparently also advises Departments on how they can overturn the will of voters by simply ignoring the legal text of citizen-initiative ballot measures in voter guides and the official question placed before voters at the ballot booth.

Two weeks after the Health Commission adopted its Resolution May 19 regarding St. Mary’s SNF closure, the City Attorney’s Office finally weighed in on June 1. In response to a separate records request, the City Attorney’s Office appears to admit the City Attorney has not issued any formal written opinions about Prop Q during the past 30 years. In addition, the CAO claims that to the extent my records request had sought communications between the Health Commission and the City Attorney, any communications (apparently including e-mails) are protected by attorney-client “privilege,” and/or by attorney “work product privilege,” and won’t be released.

This is completely Orwellian: How can the Health Commission refuse to release a secret City Attorney “opinion” granting them authority to overturn the intent of citizen-initiatives that voters passed, without going back to the voters to ask permission to rescind previously-passed legislation? How did we get to the point when voter-initiatives can be overturned using secret City Attorney “communications” the City Attorney and Health Commission refuse to disclose?

The Health Commission’s refusal to release “communications” with the City Attorney is particularly galling because it is being shrouded in complete secrecy, having been issued with no citizen oversight, demonstrating more brazen chutzpah! The City Attorney’s secret “advice” smacks of another secret court — the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court — that’s let the NSA keep spying on our phone records under the so-called “Patriot Act” passed in 2001.

What would be so

wrong with allowing citizens to read the City Attorney’s

written opinion parsing Prop Q that purportedly permits the Health

Commission broad latitude and “discretion” to simply

drop reaching a Finding of “will” or “will not”

be detrimental?

What would be so

wrong with allowing citizens to read the City Attorney’s

written opinion parsing Prop Q that purportedly permits the Health

Commission broad latitude and “discretion” to simply

drop reaching a Finding of “will” or “will not”

be detrimental?

After all, this secret City Attorney opinion — albeit Orwellian — effectively neuters Prop Q, rendering any future Prop Q hearings unnecessary. If allowed to stand, it will effectively end any need to hold Prop Q hearings, taking us right back to 1988 when private facilities could do as they pleased closing or eliminating heath care services without any community involvement and oversight.

By changing the Findings for St. Mary’s SNF closure on May 19, five of the seven Health Commissioners voted to overturn the will of 129,257 voters who passed Prop Q 27 years ago.

Only voters can rescind Prop Q, not a secret “opinion” or communication issued by the City Attorney. If the Health Commission wants Prop. Q changed, the City must go back to voters and ask them to rescind or revise it. How did the five Commissioners who passed this Resolution know better than the 129,257 voters who passed Prop Q 27 years ago? Who anointed them to gut processes in our democracy using a secret City Attorney “opinion” that trashes our democratic processes?

The Health Commission

has set a very dangerous precedent by doing so.

The Health Commission

has set a very dangerous precedent by doing so.

A Lesson from Prop “E” in 2011

Back in November 2011, Supervisor Scott Wiener managed to get Proposition “E” placed on the ballot, which would have permitted the Board of Supervisors to eventually overturn ballot measures placed on the ballot by the Mayor or Board of Supervisors three to seven years after voter approval. Voters saw through this ruse, and rejected Prop “E” by a resounding 67.1%, handing Wiener a resounding defeat, perhaps in part because voters may have feared that Wiener would have next proposed allowing the Board of Supervisors to repeal, tinker with, or otherwise alter ballot measures passed by voters that were placed on the ballot via citizen petition-signature initiatives.

What we have now

with Commissioner Chow, Director Garcia, and the City Attorney

wanting to change the intent of Prop Q is the same sort of end

run around the will of voters. Chow’s suggestion of working

with the Board of Supervisors to somehow change Prop Q is worrisome.

Prop Q cannot be changed by anyone other than the voters, but

instead of going back to voters, Chow now appears to be trying

to undo Prop Q legislatively, or by using secret City Attorney

opinions.

What we have now

with Commissioner Chow, Director Garcia, and the City Attorney

wanting to change the intent of Prop Q is the same sort of end

run around the will of voters. Chow’s suggestion of working

with the Board of Supervisors to somehow change Prop Q is worrisome.

Prop Q cannot be changed by anyone other than the voters, but

instead of going back to voters, Chow now appears to be trying

to undo Prop Q legislatively, or by using secret City Attorney

opinions.

Under the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) private hospitals will have even more incentive than in 1988 to eliminate medical services suddenly and without input from the community. A “strict” reading of Prop Q as originally enacted by the voters is actually needed now, much more than ever, to prevent the Dr. Chow’s and the Barbara Garcia’s of the world from dictating to the rest of us what the healthcare “system” should look like, and to get out of having to rule on whether service reductions will or will not have a detrimental impact on our healthcare. Without the focus being “facility centered,” you can expect private facilities to dictate to us how “patient-centered” will be defined, by whom, and without any oversight.

As you face being dumped out-of-county for skilled nursing

care following your stroke, brain injury, or heart attack, you

may find yourself asking “Please remind me again. How did

we get here?”

Monette-Shaw is an open-government accountability advocate, a

patient advocate, and a member of California’s First Amendment

Coalition. He received the Society of Professional Journalists-Northern

California Chapter’s James

Madison Freedom of Information Award

in the Advocacy category in March 2012. Feedback: monette-shaw@westsideobserver.