Westside Observer

Westside Observer September 2015 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Don’t Fall for “Blank Check” Snake Oil on San Francisco’s November 2015 Ballot

Reject the $310 Million Housing Bond

Article in Press Printer-friendly PDF file

Westside Observer

Westside Observer

September 2015 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Don’t

Fall for “Blank Check” Snake Oil on San Francisco’s

November 2015 Ballot

Reject the

$310 Million Housing Bond

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

Voters last passed a housing bond 19 years ago in 1996, but rejected

housing ballot measures in 2002 and 2004. They would be wise to

reject the $310 million Proposition A bond measure on November

3, too.

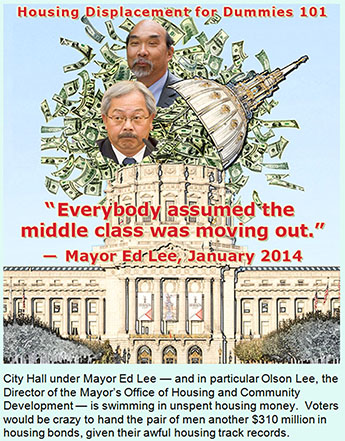

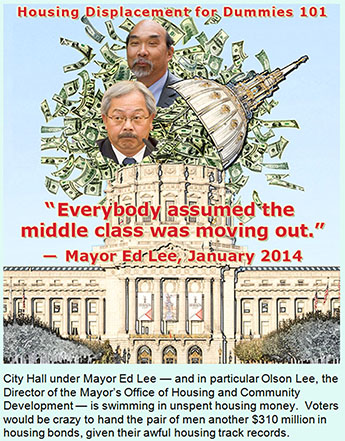

Prop. “A” is riddled with many significant problems. And it doesn’t openly inform voters that $25 million or more of the planned $80 million portion of the bond set aside for middle-income housing may be targeted to “developer incentives.”

Really? Voters are being lured into issuing bonded debt interest on Prop. A to fund developer incentives? For that reason alone, voters should reject this bond. But there’s much more to dislike about Prop. A, starting with the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD), which has a deplorable track record in its own right.

The Mayor wants you

to approve handing him another $310 million. But he doesn’t

want to tell you that as of June 30, 2015 he’s already sitting

on $95.7 million in unencumbered — unspent — funds between

the Housing Trust Fund and the separate Affordable Housing Fund.

The Mayor wants you

to approve handing him another $310 million. But he doesn’t

want to tell you that as of June 30, 2015 he’s already sitting

on $95.7 million in unencumbered — unspent — funds between

the Housing Trust Fund and the separate Affordable Housing Fund.

And the Mayor isn’t likely to tell you before you vote how much of the bond (in dollars or percent mix) is earmarked to preserve existing housing vs. building new affordable housing.

Ed Lee was appointed as mayor by the Board of Supervisors on January 11, 2011 after promising the Board that he would not run for election 11 months later in November 2011, which was a lie because he ran for election and we’ve now endured five years of Mayor Lee’s housing policies, which results have been pathetic.

In January 2014 Time magazine interviewed Mayor Ed Lee and asked him: “Why has San Francisco been so slow to build?” Lee replied:

“Our city did

pretty good in investing in low-income housing and trying to do

as much as we could for the homeless. That was where our sentiments

were … I don’t think we paid any attention to the middle

class. I think everybody assumed the middle class was [sic: were]

moving out.”

“Our city did

pretty good in investing in low-income housing and trying to do

as much as we could for the homeless. That was where our sentiments

were … I don’t think we paid any attention to the middle

class. I think everybody assumed the middle class was [sic: were]

moving out.”

Lee said this three years into his tenure as mayor. This says it all: Are all of Lee’s housing policies predicated on assumptions?

Evolving Proposed Bond Use

Like the eroding sand on Ocean Beach, the planned uses for the Affordable Housing Bond have shifted considerably, often with dizzying speed since it’s unveiling in January 2015.

The

Initial $250 Million Bond Proposal

The

Initial $250 Million Bond Proposal

As I wrote in “Mayor’s Housing Scam, Redux” in the Westside Observer’s March 2015 issue, MOHCD’s Deputy Director Kate Hartley outlined proposed uses of the then $250 million bond measure in a January 27, 2015 e-mail.

A series of e-mails obtained under public records requests included a chart in Hartley’s e-mail showing MOHCD had proposed allocating $166 million (66% of the $250 million bond) for approximately 710 low- to middle-income housing units (52.2% of the proposed 1,360 units), just $70 million for 350 middle-income housing units (25.7% of the 1,360 units), and $15 million for 300 upper-income housing units (22% of the 1,360 units) for households that conceivably earn up to $203,800 of area median income for a family of four (or up to $142,700 for a single person).

As I wrote last March, why is a general obligation bond to rebuild public housing proposing to set aside funds to build 300 units of upper-income housing for three-person households who may earn up to $183,400 (200% of AMI), or higher?

A

week after Hartley’s January 27 e-mail, the Mayor’s

Budget Director proposed a different allocation of the bond during

a meeting with the Mayor on February 3. An extract from a presentation

to the Mayor a week later on February 3 shows a second proposal that revealed a different

picture of the planned use of the $250 million bond. For starters,

while MOHCD proposed spending $30 million to accelerate and shorten

the HOPE SF public housing program schedule from 20 years to 17

years, the Mayor’s Budget Director’s presentation proposed

spending $80 million on the same acceleration of HOPE SF. After

soaring from $30 million, it remains at $80 million in the now

$310 million November bond measure.

A

week after Hartley’s January 27 e-mail, the Mayor’s

Budget Director proposed a different allocation of the bond during

a meeting with the Mayor on February 3. An extract from a presentation

to the Mayor a week later on February 3 shows a second proposal that revealed a different

picture of the planned use of the $250 million bond. For starters,

while MOHCD proposed spending $30 million to accelerate and shorten

the HOPE SF public housing program schedule from 20 years to 17

years, the Mayor’s Budget Director’s presentation proposed

spending $80 million on the same acceleration of HOPE SF. After

soaring from $30 million, it remains at $80 million in the now

$310 million November bond measure.

When the two proposals were compared side-by-side, it was clear the Mayor and his staff were throwing darts at the wall to set what would stick.

A Competing $500 Million Housing Bond

Although Supervisor

John Avalos introduced in late Spring 2015 an Affordable Housing

Bond measure for $500 million to compete against the Mayor’s

$250 million measure, scant details ever surfaced detailing how

Avalos’ measure would allocate proceeds of the doubled bond

amount.

Although Supervisor

John Avalos introduced in late Spring 2015 an Affordable Housing

Bond measure for $500 million to compete against the Mayor’s

$250 million measure, scant details ever surfaced detailing how

Avalos’ measure would allocate proceeds of the doubled bond

amount.

Avalos’ measure, however, forced the Mayor and Board of Supervisors to negotiate over the final bond amount to be placed before voters, which grew into a piddley $60 million increase to the $310 million compromise that voters will consider on November 3.

Avalos’ negotiations appear to have only cleared up the vague categories of just three major areas of spending of the then-$300 million measure that was initially vaguely itemized in an MOHCD PowerPoint presentation dated June 10. The presentation potentially suggested spending $50 million to $100 million for public housing, $50 million to $200 million for affordable housing for those earning up to 80% of area median income (AMI), and $25 million to $100 million for middle-income housing for those earning 80% and above of AMI — all of which added up to $400 million in potential spending, somehow magically dividing the loaves of ranges of spending on a then-$300 million bond measure, calling into question MOHCD’s competency with basic math.

Avalos managed to

get $50 million added for a fourth proposed use to acquire sites

in the Mission District, and rather than ranges of dividing the

loaves, he managed to get MOHCD to commit to maximum amounts for

each of four categories, rather than ranges of spending that also

would have been left to MOHCD’s sole discretion to determine.

Avalos managed to

get $50 million added for a fourth proposed use to acquire sites

in the Mission District, and rather than ranges of dividing the

loaves, he managed to get MOHCD to commit to maximum amounts for

each of four categories, rather than ranges of spending that also

would have been left to MOHCD’s sole discretion to determine.

A Compromise: Vague $310 Million Final Bond

Unfortunately, language in the official ballot measure is completely vague and does not itemize precisely or accurately how the bond will eventually actually be spent. Although there is no clause in the bond language giving the Mayor’s Office of Housing sole discretion over how the bond money will be spent, you can be assured that’s what will happen, since MOHCD has no Board or Commission providing oversight on the entire MOHCD, and since sole discretion over spending of the Housing Trust Fund was handed to MOHCD by voters in 2012.

Prop. A’s legal

text says $310 million “may be

allocated” to various uses, not “shall

be spent on …” handing broad spending

discretion to the Mayor’s Office of Housing (MOHCD) —

which has no Commission providing oversight. Prop. “A”

amounts to handing Mayor Lee and Olson Lee a $310 million blank

check to spend as they please.

Prop. A’s legal

text says $310 million “may be

allocated” to various uses, not “shall

be spent on …” handing broad spending

discretion to the Mayor’s Office of Housing (MOHCD) —

which has no Commission providing oversight. Prop. “A”

amounts to handing Mayor Lee and Olson Lee a $310 million blank

check to spend as they please.

The Mayor’s official Proponent argument that will be printed in the November 2015 voter guide comically claims that “not one cent” will be spent on luxury housing from the $310 million bond. Don’t believe the Mayor’s “not one cent for luxury housing” claim.

Background documents to the $310 million bond — but not included in the actual legal text of the measure — now claim $80 million is targeted for public housing, $50 million is targeted for site acquisition and unit rehabilitation in the Mission District, $100 million is targeted for low-income housing, and $80 million is targeted for middle-income housing.

The background documents do not reveal how much of the bond is to preserve existing housing vs. building new affordable housing, but huge chunks of the $80 million targeted for public housing involves existing housing that needs to be “preserved.” It’s also not known how much of a separate $80 million targeted for middle-income housing is being dedicated to preserving existing housing in the “Expiring Regulations” category, either.

The Mayor’s

first draft of Prop. “A” indicated it would mostly fund

public housing and market rate housing. Without the word “shall”

included in Prop. A’s legal text, market rate — not

affordable — housing will more than likely be built.

The Mayor’s

first draft of Prop. “A” indicated it would mostly fund

public housing and market rate housing. Without the word “shall”

included in Prop. A’s legal text, market rate — not

affordable — housing will more than likely be built.

Affordable Housing Becomes Unaffordable as Housing Contracts Expire

Ignore for a minute that MOHCD will have sole discretion over spending on this bond measure. Although Avalos managed to get MOHCD to commit to specific planned uses of the $310 million bond measure, two troublesome areas remain within the $80 million “Middle Income” planned uses of the bond.

The first problem with the “middle income” category involves funding for “Expiring Regulations Preservation.”

An article titled “When Affordability Expires: The Battle Over Covenant Housing Contracts” by Noah Arroyo in the August 20, 2015 issue of SF Weekly [the same article titled “Past Due” in SF Weekly’s print edition] begins to tell the story of affordable housing that becomes unaffordable when government contracts issued decades ago begin to expire.

Arroyo’s article

reports that many apartment buildings — including the South

Beach Marina Apartments — were built partially with San Francisco’s

Redevelopment Agency [a.k.a. Housing Authority] money in contractual

“covenants” with private developers that designated

various percentages of the housing to be affordable housing during

the length of the contracts.

Arroyo’s article

reports that many apartment buildings — including the South

Beach Marina Apartments — were built partially with San Francisco’s

Redevelopment Agency [a.k.a. Housing Authority] money in contractual

“covenants” with private developers that designated

various percentages of the housing to be affordable housing during

the length of the contracts.

Now that some of the contracts are expiring, building owners are allowed to jack up rents from affordable to market rate. Sophie Hayward, Deputy Director of MOHCD noted to Arroyo that at least four buildings throughout the City have contracts that are set to expire between March 2016 and January 2021. Hayward says MOHCD’s goal is “to find strategies so that no tenants are displaced as a result of expiring covenants.” Hayward also noted the City can’t force building owners to maintain below-market rate rents when the contracts expire.

When MOHCD was asked by this columnist for a list of each property for which Expiring Regulations Preservation is being sought, including the property’s name, location, and the number of units anticipated to be preserved — which list the City and MOHCD surely must have had readily available since they’ve made this a cornerstone of the $310 million housing bond measure — MOHCD instantly invoked the need for a 14-day extension, claiming it needsed to consult with another City department. Another needless delay responding to basic records requests by the smug folks running MOHCD. When MOHCD finally responded on September 1, it turns out there are five buildings MOHCD is aware of, with a total of 624 units that are set to expire between January 2015 and January 2021. MOHCD provided the names of the five buildings, but noted that “at this time, there is no list of buildings for which bond funds are being sought.”

Closely related to the SFWeekly article on the loss of affordable housing units, is an article by Emily Green published in the San Francisco Chronicle on July 14, 2015, “Twist in Rent Flap: City’s the landlord,” involving the Midtown Park Apartments near Geary and Divisadero. The building, which is owned by the City, was leased to a non-profit that deferred maintenance for years, which resulted in the property being so in need of repairs it couldn’t qualify for insurance.

The City acquired

Midtown Park Apartments in 1968 during a foreclosure, and leased

it to Midtown Park Corporation, a nonprofit composed of tenants.

After 40 years of the City maintaining little to no oversight

of the property, the City was “essentially an absentee landlord

while the property cycled through various property managers,”

Ms. Green reported. Apparently successive property managers failed

to perform necessary repairs, and so did the City, until the City

became upset in 2013 that it was paying $200,000 in maintenance,

leading the City to terminate Midtown Park Corp.’s lease.

The City acquired

Midtown Park Apartments in 1968 during a foreclosure, and leased

it to Midtown Park Corporation, a nonprofit composed of tenants.

After 40 years of the City maintaining little to no oversight

of the property, the City was “essentially an absentee landlord

while the property cycled through various property managers,”

Ms. Green reported. Apparently successive property managers failed

to perform necessary repairs, and so did the City, until the City

became upset in 2013 that it was paying $200,000 in maintenance,

leading the City to terminate Midtown Park Corp.’s lease.

Now residents are facing stiff rent increases by the City to generate income to pay for repairs. While Midtown Park is not public housing, it is city-owned apartment housing. Even Supervisor London Breed noted it is not private property, but is “subsidized taxpayer-dollar housing,” and indicated she supports the City’s rent hikes.

Amazingly, the City now claims that the Rent Control Ordinance does not apply to city-regulated property. How many other City-subsidized properties does the City and MOHCD’s director consider to be exempt from rental control?

Green quotes Olson Lee, MOHCD’s director, who said claims that the City is exploiting tenants is “very insulting,” and the City’s long-term goal is to preserve Midtown Park units as affordable housing. Mr. Lee appears to ignore that a short-term goal should be to keep these current residents in their homes to avoid permanent displacement. And some tenants see the rent increases as moving to market-rate rents, even though the City counts on the subsidized housing as a way to earn federal payments to support low-income people.

Middle

Income Carve-Out for “Expiring Regulations Preservation”

Middle

Income Carve-Out for “Expiring Regulations Preservation”

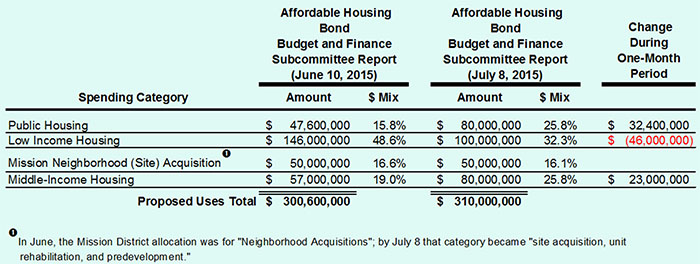

Background file #150489 posted as the packet to the Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Committee hearing on June 23 showed that when the bond measure was being vetted for $300 million in a PowerPoint presentation dated June 10, 2015 prepared by the Affordable Housing Bond’s Budget and Finance Subcommittee, a subtotal of $57 million was initially earmarked for “middle-income housing,” including $25 million of the $57 million for “Expiring Regulations Preservation” on page 26 of the background file.

Three weeks later, background file #150490 posted as the packet for the Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Committee hearing on July 14 showed the bond measure was being increased to $310 million in a report from the Mayor’s Office titled “$310 Million Affordable General Obligation Bond Report.” Page 9 of Mayor’s report increased the subtotal earmarked for “middle-income housing” to $80 million (from $57 million shown just a few weeks earlier in the PowerPoint presentation, a $23 million increase), including “Expiring Regulations Preservation” on page 37 of the second background file, but the July 14 background file did not show the dollar amounts being allocated to each of the sub-category dollar amounts within the increased “Middle-Income Housing” section.

MOHCD did not respond by press deadline for this article providing information on whether the Expiring Regulations Provision allocation was increased beyond the $25 million reported in the June 10 PowerPoint presentation, although MOHCD did respond after deadline on September 1 and provided a list of which properties, by location, may potentially be at risk, including 624 housing units. After being pushed following this article’s deadline for further information, MOHCD claimed on September 4 that it has no records about how the $23 million increase to “Middle-Income Housing” section will be allocated within the new $80 million amount, or whether any of the increase will be allocated to expiring regulations preservation.

But MOHCD asserted on September 1 there is no list of buildings for which bond funding is actually being sought, and offered no explanation of why had it earmarked $25 million of the $310 million bond measure in its June 10 PowerPoint presentation to “preserve” this housing. It’s odd that MOHCD has no apparent plan to allocate funds for preserving this housing, but may be setting aside $25 million for potentially-at-risk units in the future.

The second problem with the $80 million “middle income” set-aside in the bond involves apparent “developer incentives,” with no details explaining the so-called incentives. How did we get to having to incentivize developers?

In the same background file #150490 packet for the Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Committee hearing on July 14, Ted Egan, the City’s Chief Economist who serves in the Office of Economic Analysis in the City Controller’s Office, blabbed that the middle-income category includes developer incentives.

Specifically, Egan has been asked what portion (in dollar amount, or percentage) of the $80 million of the down-payment portion of this bond is being set aside, or allocated to, “developer incentives,” and what form of incentives are being considered or planned. In response to the public records request, Egan also invoked a 14-day extension in which to respond, claiming he needed to consult with another City department before responding. A reasonable person might assume such developer incentives would already be documented and readily available, given they appear to have been factored into the proposed bond’s proposed uses.

Egan responded after this article went to press; but did not provide precise information on what developer incentives may be included. Discussion of Egan’s response was added as a Postscript to this article after it was published.

Mayor's Rotten Record of Housing Production

As I noted in “Housing Withers on the Vine” in the Westside Observer’s May 2015 issue, San Francisco’s 2013–2014 Civil Grand Jury released a report in June 2014 titled “The Mayor’s Office of Housing: Under Pressure and Challenged to Preserve Diversity.” In discussing challenges facing MOHCD, the Grand Jury wrongly noted that the Housing Trust Fund (HTF) — “may need to provide stabilization funding to the Housing Authority for emergency repairs,” but then offered a caveat:

The Jury’s report

noted its policy concerns for affordable housing parity and fair

distribution of housing built for all income tiers. Looking at

it by household income as a percentage of Area Median Income (AMI),

the Jury noted in Table 1 that the City achieved 113% of market

rate housing (those earning greater than 120% of AMI between 2007

and 2014 identified in the Regional Housing Needs Allocation goals,

a state-mandated planning document.

The Jury’s report

noted its policy concerns for affordable housing parity and fair

distribution of housing built for all income tiers. Looking at

it by household income as a percentage of Area Median Income (AMI),

the Jury noted in Table 1 that the City achieved 113% of market

rate housing (those earning greater than 120% of AMI between 2007

and 2014 identified in the Regional Housing Needs Allocation goals,

a state-mandated planning document.

During the same eight-year period — in which Mayor Lee has served for five of those eight years — the City achieved 65% of housing for extremely-low and very-low households (those earning less than 50% of AMI). But the City only produced 16% of the housing goal for low-income earners (50% to 79% of AMI), and 25% of housing needs for moderate-income earners (80% to 120% of AMI).

Then, the Planning Department’s April 9, 2015 2014 Housing Inventory Report revealed a host of data that is disturbing, at best.

In an introductory highlight titled “2014 Snapshot,” Planning reports there was a net addition of 3,514 total units to the City’s housing stock in (presumably) calendar year 2014 — with Ed Lee as Mayor in 2014 — but only 757 of them (just 21.5%) were new “affordable housing” units. Clearly, the 21.5% figure is far short of the Mayor’s stated policy goals and the November 2014 Prop “K” declaration of policy adopted by voters for 33% of affordable units for low-and moderate-income households, let alone the goal of 50% to be affordable for middle-class housing.

Table A-2 in Planning’s Housing inventory Report lists another 12 major affordable housing projects completed in 2014, totaling an additional 431 units, all of which are rental units for very low-income or low-income — and none for middle-income — households.

Out-of-Whack Affordable Housing Balance

The new Housing Balance Report also indicates only 21% of housing built between 2005 and 2014 were “affordable”; only 11% in the upcoming housing pipeline will be “affordable.”

Supervisor

Kim’s Proof-in-the-Pudding: Housing Balance Report

Supervisor

Kim’s Proof-in-the-Pudding: Housing Balance Report

Next, on July 7, 2015 the Planning Department released its new Housing Balance Report mandated by passage of Prop. “K” on the November 2014 ballot. Readers may recall that leading up to the July 2014 deadlines to place ballot measures on the November 2014 ballot, Supervisor Jane Kim had proposed a ballot measure to codify via a City Ordinance that 33% of new housing construction had to be affordable throughout the City.

She was snookered by the Mayor, who strong-armed Kim into watering down her measure to a fairly useless non-binding “Declaration of Policy,” which carries no force in law. The measure Kim eventually placed on the November 2014 ballot merely regurgitated the Mayor’s policy goals of creating 30,000 units of housing by the year 2020, which he had already announced as a policy goal in his January 2014 State-of-the-City speech. Voters didn’t really need to vote to approve a mere “goal” that the Mayor had already, albeit belatedly, made part of his so-called “affordability agenda.”

The Housing Balance Report from Planning notes that the first calculation to determine housing balance (the “balance” between market rate vs. affordable housing) involves the “Cumulative Housing Balance” over a ten-year period citywide, calculating new housing built, plus acquisition and “substantial” rehabilitation of affordable units, plus planned but not-yet-built units that have gained both Planning Department approval and Department of Building Inspection (DBI) permits to proceed with construction, minus units removed from protected status.

The first calculation for “Cumulative Housing Balance”

stood at just 21%, far short of Kim’s hoped-for 33% affordable

mandate. The main reason was that although 6,559 new affordable

housing units were built during the 10-year period, fully 5,470

units were removed from protected status due to demolition, El lis Act evictions,

owner move-in evictions, condo conversions, and other “no-fault”

reasons.

lis Act evictions,

owner move-in evictions, condo conversions, and other “no-fault”

reasons.

The second calculation for “Projected Housing Balance” includes residential projects that have received approval from the Planning Commission, but have not yet started construction, perhaps awaiting DBI permits.

The second calculation of the “Projected Housing Balance” pipeline is a mere 11% are projected to be affordable — anemic, when not utterly pathetic. The $310 million Affordable housing bond measure may be targeted or spending just 11% of it for affordable housing in the pipeline. The other 89% of the bond may be targeted to non-affordable housing projects.

But that’s citywide data. The data varies and worsens by District, with six of the eleven City districts — Districts 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 11 — having negative Cumulative Housing Balance (meaning loss of affordable housing units) over the past ten years.

And of the “Projected Housing Balance” projected in the upcoming pipeline, just 421 (11.2%) of the net 3,771 units will be affordable, but only in three of the City’s districts (Districts 2, 3, and 6) even at the same time that the other eight City districts have zero “affordable” units currently permitted.

Across the City’s 11 Supervisorial Districts, of the 421 “affordable” units in the housing balance projection none are for “very low income,” 326 (8.6% of the 3,771 net new units) are for “low income” households, and just 95 (8.6% of the 3,771 net new units) are for “moderate income” households. The 421 units are only in Districts 2, 3 and 6.

The remaining 3,350 (88.2%) of the 3,771 units in the upcoming Projected Housing Balance pipeline are apparently planned as market-rate units. The imbalance of market-rate housing in the projected pipeline is one symptom that we may need a citywide moratorium on market-rate housing development until the affordable housing balance is restored to true balance.

Clearly, the out-of-balance projected housing skewed in favor of market-rate development will occur under Mayor Ed Lee’s watch, and will likely to be touted as an important victory for Lee and his backers, such as billionaire Ron Conway.

Because the Board

of Supervisors went on summer recess during August, it isn’t

known whether there will be a public hearing on the Housing Balance

Report in September, or how soon a hearing will be scheduled and

held.

Because the Board

of Supervisors went on summer recess during August, it isn’t

known whether there will be a public hearing on the Housing Balance

Report in September, or how soon a hearing will be scheduled and

held.

Swimming in Housing Money

As I wrote in “Affordability Mayor: A Housing Bait and Switch?” in the Westside Observer’s April 2014 issue, in November 2012 voters passed Proposition “C” creating a Housing Trust Fund (HTF) that will divert $1.34 billion to $1.5 billion from the General Fund to HTF over the next 30 years, handing MOHCD sole discretion over HTF spending. MOHCD admitted 83.7% — $16,744,000 — of HTF’s first-year $20 million allocation was unspent.

The 2012 voter guide never clearly told voters $1.34 billion would be provided to the HTF. Still, lured by the smell of money, voters passed Proposition “C” all but ignoring that it contained a poisoned pill buried in the legal text of the initiative: For certain residential projects beginning after January 2013, the City would be required to reduce — by a staggering 20 percent — the current on-site inclusionary housing obligations of developers to develop “affordable” inclusionary housing. The poison pill, of course, was included under Mayor Lee’s watch in Room 200.

The Mayor gave MOHCD authority in 2014 to borrow up to $25 million annually against future-year HTF revenue allocations, but MOHCD asserted on September 1 that it has not yet acted on the borrowing authority in Fiscal Years 14–15, 15–16, and 16–17. MOHCD could have borrowed $75 million against future year revenue but hasn’t done so. Does MOHCD not understand that there’s a housing crisis going on now and it should act with some haste?

The Board of Supervisors just approved last June issuing $50 million (plus interest) in “certificates of participation” (COP’s) (without voter approval) for the HTF’s HUD rental assistance program. The City’s projected HTF budget shows $25 million is earmarked for COP’s in the current Fiscal Year (2015–2016) and another $25 million is budgeted in Fiscal Year 2016–2017, plus another $6 million across the two years for costs of issuing the COP’s.

Developers have paid

$176.7 million in inclusionary housing fees; $45.9 million remained

unspent by June 2014.

Developers have paid

$176.7 million in inclusionary housing fees; $45.9 million remained

unspent by June 2014.

The Board of Supervisors Budget and Legislative Analyst — Harvey Rose’s consultancy — uncovered in 2014 MOHCD couldn’t account for $2 million in rent stabilization funds. San Francisco’s 2013–2014 Civil Grand Jury report is a damning indictment of MOHCD’s lack of transparency and miserable recordkeeping. This August, MOHCD admitted it hadn’t created an electronic database of loans issued under its Downpayment Assistance Loans Program (DALP) between 1998 and 2012, and only began building an electronic database at some point during 2012.

As I reported in “Housing Withers on the Vine” last May, in addition to the $1.5 billion Housing Trust Fund, and the separate Affordable Housing Fund, MOHCD is involved in hundreds of millions of dollars in housing projects to rebuild the City’s public housing.

On April 8, 2015 the Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Sub-Committee meeting included 14 separate agenda items to rehabilitate residential rental housing projects throughout the City that will be funded by floating housing revenue bonds (that don’t require voter approval to issue). The 14 projects committed $544 million in housing revenue bonds to rehabilitate 1,424 units believed to be public housing.

Two weeks later, on April 28 the full Board of Supervisors agenda included a multifamily housing revenue note for an additional $61.4 million to construct another 200 rental units at 588 Mission Bay Boulevard North. That brings the total to $605.4 million in just a one-month period for revenue bonds and revenue notes for a total of 1,624 units believed to be public housing, only 200 of which are “new” units.

Between the HTF,

and the housing revenue bonds, MOHCD is playing with over $2 billion

in funny money, at a minimum, with spending at its sole discretion.

Between the HTF,

and the housing revenue bonds, MOHCD is playing with over $2 billion

in funny money, at a minimum, with spending at its sole discretion.

$95 Million in Unencumbered Housing Funds

The City has at least two trust funds set up for affordable housing production, including the Housing Trust Fund (HTF) created by voters in November 2012, and the separate Affordable Housing Fund (AHF).

Records provided by the City Controller’s Office showing the actual vs. budgeted performance for the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2015 paints a disturbing picture, since between the two funds, the City — Mayor Lee and MOHCD Director Olson Lee — ar sitting on $95.745 million in unencumbered (unspent) funds.

As the HTF budget shows, although the City issued a total of $27.1 million in “Loans Issued by the City,” the HTF budget left $9.36 million unencumbered at the end of the fiscal year. The $27.1 million in loans issued from the HTF were $3.37 million more than the $23.8 million budgeted for issuing loans. The budget actual show the “Community Based Organization Services” line item left $1 million on the table in unencumbered funds, which may or may not have been used to supplement the loans issued, but the budget doesn’t show where the additional $2.3 million awarded for additional loans may have came from. The $3.37 million overage does not appear have come from a pot of $11.4 million in funds that had been carried forward from the previous fiscal year, since the report shows the $11.4 million still remains unencumbered.

It is not yet known

whether these loans are for only DALP (downpayment assistance)

loans, or possibly for other types of loans for non-DALP loans.

But it is clear that MOHCD does as it wishes at its sole discretion,

even if that means fiddling with its budget planning.

It is not yet known

whether these loans are for only DALP (downpayment assistance)

loans, or possibly for other types of loans for non-DALP loans.

But it is clear that MOHCD does as it wishes at its sole discretion,

even if that means fiddling with its budget planning.

Things get worse with the Affordable Housing Fund (AHF). The AHF budget shows a whopping $86.38 million in unencumbered funds at the end of June 2015, $60 million of which were unencumbered funds brought forward to the FY14–15 budget from previous fiscal years. The AHF budget had also included a line item for “Loans Issued by City” in the amount of $43.13 million, but by the end of the FY in June, $21.37 million — fully half of the line item — remained unencumbered, as if the City couldn’t find anyone, or any agency, to issue loans to.

So we have the sorry situation of $95.74 million between the HTF and AHF remaining unencumbered in the midst of an affordable housing crisis, demonstrating a potential lack of competence by housing experts on the Mayor’s staff.

These are the same people who say ”trust us” and who want voters to hand them another $310 million for vague promises to allocate the bond funds for building various types of affordable housing. Really?

Cautionary

Voices

Cautionary

Voices

San Francisco Supervisor Scott Wiener — largely viewed as the Mayor’s chief cheerleader — has screeched over and over during City Hall hearings, in the press, and at meetings of the DCCC (San Francisco’s Democratic Central County Committee) that “We need all types of housing built in San Francisco,” or words to that effect.

But there are other voices that thoughtfully note that the glut of market-rate housing being built — apparently the only type of housing that developers are willing to build without massive public sector “incentives” and subsidies, given market-rate housing sales are a powerful incentive to build — is actually making the affordable housing crisis even worse.

But the thoughtful voices of others just can’t get through to Wiener and his ilk, or to the Mayor.

First, one article by Tim Redmond on 48Hills.org on April 14, 2014 noted that the Housing Trust Fund will only account for just 10% of new affordable housing, were the City to mandate that 30% of all new housing be affordable (and which the new Housing Balance Report shows is not being implemented).

Supervisor Kim’s proposed ballot measure in April 2014 had hoped to require that whenever affordable housing production fell below 30%, that developers would have to go through additional hoops at the Planning Department to obtain permits for their market-rate housing projects, and the Planning Commission would have to justify how new market-rate housing would help balance affordable housing needs.

But Kim was beguiled by the Mayor, and instead of placing a firm ballot measure requiring this, she was snookered into placing the useless, nonbinding Declaration of Policy on the November 2014 ballot, instead.

Redmond noted that

with for-profit developers building most of the housing in San

Francisco, the small amount of “inclusionary housing”

for new affordable units simply won’t solve the problem.

Scott Wiener turned another deaf ear.

Redmond noted that

with for-profit developers building most of the housing in San

Francisco, the small amount of “inclusionary housing”

for new affordable units simply won’t solve the problem.

Scott Wiener turned another deaf ear.

On June 14, Redmond published another article indicating why market-rate housing makes the affordable housing crisis even worse. He reported on June 24, 2015 that an op-ed in the San Francisco Examiner had explained how market-rate housing construction is not the main source of financing for affordable housing. Redmond noted that the moratorium on luxury housing in the Mission District “won’t in any way damage affordable housing production.”

According to Redmond, during a debate over the Moratorium in the Mission, Supervisor Wiener again “argued that stopping market-rate housing would cut off essential funding for below-market rate units.” Redmond reports that the City’s own data shows the money from inclusionary below-market rate funding is just sucked up mitigating impacts that the market-rate luxury housing creates, resulting in no net new affordable housing.

It’s a concept totally lost on Wiener and the DCCC, which voted to oppose the “Moratorium in the Mission,” Prop. “I,” Suspension of Market-Rate Development in the Mission District on November’s ballot.

The op-ed Redmond referred to — “Don’t Believe the Hype: Affordable Housing does NOT Depend on Market Rate Development” — was written by Peter Cohen and Fernando Marti, and published in the Examiner on June 14. Cohen and Marti are co-directors of San Francisco’s Council of Community Housing Organizations.

The pair asserted

developers and cheerleaders at City Hall [think Scott Wiener]

have started a new myth that affordable housing is dependent on

market-rate housing development, with an argument that inclusionary

fees paid by market-rate developers are an “essential revenue

source for affordable housing and without them our affordable-housing

supply pipeline might come to a standstill.”

The pair asserted

developers and cheerleaders at City Hall [think Scott Wiener]

have started a new myth that affordable housing is dependent on

market-rate housing development, with an argument that inclusionary

fees paid by market-rate developers are an “essential revenue

source for affordable housing and without them our affordable-housing

supply pipeline might come to a standstill.”

Cohen and Marti say that’s nonsense, because the myth “conveniently ignores the fact that inclusionary fees on residential development are not even at the level of a ’nexus’ to simply mitigate the demand for new affordable housing.” The authors note that the City’s own housing production data illustrates how false cheerleader Wiener’s myth is, “housing balance” actually produced in 2014 was terrible, and on balance, affordable housing production got worse. They note the myth of affordable housing being dependent on market-rate development fees is a “clever but inaccurate distraction.”

Mr. Cohen authored another article on August 18, 2015, titled “A leading voice on urban planning in CA debunks housing trickle down.” In it, he disproves claims made by Gabriel Metcalf, the president of SPUR, who wrongly blamed San Francisco’s progressives for the City’s housing affordability crisis. And Cohen noted that William Fulton — who is considered to be California’s guru of city and urban planning, and is a former Mayor of Ventura —clearly debunked the simplistic argument that increasing market-rate housing supply will stabilize housing prices.

In an article titled “Insight: Does Supply Create Its Own Demand?” published July 27, 2015 on the California Planning and Development Report web site, Fulton notes that “The problem is that under some market conditions, more supply doesn’t lead to market equilibrium because it actually creates its own demand.” Fulton says that by building more market-rate housing, you just accelerate the cycle of rising demand.

Cohen thanked Fulton as being California’s top planner for debunking Metcalf’s theory of trickle-down housing policy. It’s too bad that Supervisor Wiener just won’t get this false trickle-down theory out of his head.

Other Concerns

There are at least

three other areas of concern.

There are at least

three other areas of concern.

Billionaires Club Doesn’t Contribute to Housing Development

First, according to the Forbes magazine list of billionaires published in February 2014, the Bay Area is home to 71 billionaires whose combined net worth totals a staggering $371 billion. The $310 million bond measure represents less than one-tenth of one percent of the $371 billion. San Francisco alone had 29 billionaires in 2014 having a combined net worth totaling $156 billion (of the $371 billion); the $310 million bond measure represents just two-tenths of one percent of the San Francisco Billionaires Club member’s net worth.

For that matter, five of San Francisco’s 29 billionaires — Dustin Moskovitz (Facebook), Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook), Larry Ellison (Oracle), Marc Benioff (SalesForce), and Ron Conway (founder of the Angel Investors LP funds) — have a combined net worth of $91.4 billion. And that’s not counting Uber cofounders Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick, and Airbnb cofounders Nathan Blecharczyk, Brian Chesky, and Joe Gebbiam, all five of whom reportedly became billionaires in 2015. The now three Airbnb billionaires have caused much of the displacement in San Franciscans from long-term rental housing units being converted into short-term rental units as their preferred business model.

Wikipedia, it should be noted, reports that Conway was involved in a conflict with other angel investors in the Angelgate scandal of 2010 and 2011, just at the same time Mayor Lee was appointed as the interim “caretaker” Mayor of San Francisco. “Angelgate” was a controversy surrounding allegations of price fixing and collusion among a group of ten angel investors in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Wikipedia also reports

Conway raised $600,000 for Lee’s 2011 election campaign through

independent expenditure committees, but since then questions have

been raised about whether Lee has taken actions to benefit companies

in which Conway has investments, including sf.citi (San Francisco

Citizens Initiative for Technology and Innovation), a 501(c)6

non-profit organization that advocates for the technology community.

The same technology companies who have gutted San Francisco’s

housing market.

Wikipedia also reports

Conway raised $600,000 for Lee’s 2011 election campaign through

independent expenditure committees, but since then questions have

been raised about whether Lee has taken actions to benefit companies

in which Conway has investments, including sf.citi (San Francisco

Citizens Initiative for Technology and Innovation), a 501(c)6

non-profit organization that advocates for the technology community.

The same technology companies who have gutted San Francisco’s

housing market.

Conway contributed heavily to defeat Supervisor David Campos in his bid for election to the California Assembly, and is now investing heavily in efforts to defeat the November ballot measure to restrict Airbnb rentals, since Conway invests significantly in Airbnb. Conway also contributed to then-Supervisor David Chiu’s campaign for the Assembly, after Chiu rammed through the Board terrible regulations governing Airbnb’s operations in San Francisco.

Many of these “tech” Billionaires Club members have stood by while their employees have driven up the high cost of housing in San Francisco that has led to widespread displacement of longtime San Franciscans. Although these billionaires have dipped into their philanthropy wallets for such things as a $6.8 million donation to MUNI for free rides for children, and donations to the San Francisco Unified School District and San Francisco General Hospital, they don’t appear to have contributed on dime towards funding new housing in San Francisco, preferring to let their employees take over the existing housing market, resulting in widespread displacement.

Why

should taxpayers foot this $310 million bond measure, while the

billionaires contribute nothing to funding housing development?

Since Airbnb is gutting San Francisco’s housing market, shouldn’t

it contribute to housing development costs, too?

Why

should taxpayers foot this $310 million bond measure, while the

billionaires contribute nothing to funding housing development?

Since Airbnb is gutting San Francisco’s housing market, shouldn’t

it contribute to housing development costs, too?

As Paul Krugman noted in a New York Times Op-Ed on August 17, 2015 “… the rich are politically different from you and me.” Apparently their politics involves not contributing to housing development, even for their own employees.

Bay Area Cities Piggyback on San Francisco’s Housing Bond

Second, voters need to consider the fact that while San Francisco’s City Hall is floating this “affordable housing bond,” it is thought few other Bay Area cities are sponsoring their own housing bond measures, content to let San Francisco carry the water.

There has been a large growth rate of middle- and upper-class families who have settled in cities like Palo Alto, Los Altos, Portola Valley, Woodside, and Atherton as part of the technology boom of Silicon Valley. But there’s no evidence these five cities have placed ballot measures before their voters to obtain bond financing for affordable housing construction in any of the five cities.

Other Peninsula cities

— including Belmont, Brisbane, Burlingame, Colma, Cupertino,

Daly City, East Palo Alto, Foster City, Half Moon Bay, Hillsborough,

Menlo Park, Millbrae, Mountain View, Pacifica, Redwood City, Redwood

Shores, San Bruno, San Carlos, San Mateo, and South San Francisco

— may be counting on San Francisco to develop housing that

tech company employees working in their cities will then snap

up, exacerbating the loss of affordable housing in San Francisco.

Other Peninsula cities

— including Belmont, Brisbane, Burlingame, Colma, Cupertino,

Daly City, East Palo Alto, Foster City, Half Moon Bay, Hillsborough,

Menlo Park, Millbrae, Mountain View, Pacifica, Redwood City, Redwood

Shores, San Bruno, San Carlos, San Mateo, and South San Francisco

— may be counting on San Francisco to develop housing that

tech company employees working in their cities will then snap

up, exacerbating the loss of affordable housing in San Francisco.

Why should San Francisco voters bear the burden of this bond, which may well benefit employers and their employees located in Silicon Valley and other Peninsula cities?

Raiding the City's Pension System to Fund Housing

Third, Mayor Lee has been attempting to strong arm the San Francisco Employees Retirement System (SFERS) into a dubious $125 million investment in MOHCD’s DALP loan pool, even while he’s already poised to collect $2.26 billion in anticipated housing revenue that may be being badly managed by MOHCD.

Excluding the $310

million housing bond measure, the proposed ten-year $125 million

investment from the pension fund would augment other sources of

funding flowing into the $1.3 billion HTF over the next 20 to

30 years, including: $605 million just floated for public housing

lease revenue bonds; $50 million will be issued in “certificates

of participation” (that involves paying interest on the $50

million) for the HTF’s HUD rental assistance demonstration

(RAD) program in the current fiscal year and the following fiscal

year; a combined total of $176.68 million of developer fees collected

to date — including $73.995 million from the affordable housing

jobs-housing linkage fees of, and another $89.42 million in Affordable

Housing Inclusionary Program fees, with more likely to be earned

— and an unclear amount of other potential funds flowing

to the current Affordable Housing Fund and the Housing Trust Fund.

Excluding the $310

million housing bond measure, the proposed ten-year $125 million

investment from the pension fund would augment other sources of

funding flowing into the $1.3 billion HTF over the next 20 to

30 years, including: $605 million just floated for public housing

lease revenue bonds; $50 million will be issued in “certificates

of participation” (that involves paying interest on the $50

million) for the HTF’s HUD rental assistance demonstration

(RAD) program in the current fiscal year and the following fiscal

year; a combined total of $176.68 million of developer fees collected

to date — including $73.995 million from the affordable housing

jobs-housing linkage fees of, and another $89.42 million in Affordable

Housing Inclusionary Program fees, with more likely to be earned

— and an unclear amount of other potential funds flowing

to the current Affordable Housing Fund and the Housing Trust Fund.

That adds up to the Mayor already being on target to collect, at a minimum, $2.26 billion for housing without needing this $310 million housing bond measure.

And each of these funds may be awarded additional funds in future years, so nobody knows yet how much higher the $2.26 billion will grow.

MOHCD and its Director Olson Lee appear to have an insatiable appetite to latch on to funding however they can, even if it means raiding funds that City employees and retirees are counting on to fund their retirements.

In June 2014, Supervisor

Cohen first floated an idea to convince SFERS to invest $25 million

to $50 million in the DALP loans, but her initial request was

inflated by the Mayor to a $125 million request. Fully 14 months

later, SFERS’ Board of Directors hasn’t approved any

such investment, and for good reason.

In June 2014, Supervisor

Cohen first floated an idea to convince SFERS to invest $25 million

to $50 million in the DALP loans, but her initial request was

inflated by the Mayor to a $125 million request. Fully 14 months

later, SFERS’ Board of Directors hasn’t approved any

such investment, and for good reason.

At the start of SFERS June 10, 2015 Board of Directors meeting, a joint press release issued by Mayor Lee and Supervisor Malia Cohen dated the same date claimed that “under terms of a resolution to be introduced today,” it was all but a done deal that SFERS would approve investing the $125 million in the DALP loan pool over a ten-year period, ostensibly to “provide loans for up to 1,500 middle-class San Francisco families over the next decade.”

The press release wrongly claimed in its first paragraph:

The press release

created an uproar among current and retired City employees, and

disturbed Commissioners of the Retirement Board, because at that

point SFERS’ Board had not even been presented with a completed

due diligence analysis of the potential investment that SFERS’

Investment Division staff had been analyzing for at least nine

months, dating back to December 2014. SFERS’ Board only received

the sales pitch — itself a shocker — during its July

meeting, which contradicted the premature press release.

The press release

created an uproar among current and retired City employees, and

disturbed Commissioners of the Retirement Board, because at that

point SFERS’ Board had not even been presented with a completed

due diligence analysis of the potential investment that SFERS’

Investment Division staff had been analyzing for at least nine

months, dating back to December 2014. SFERS’ Board only received

the sales pitch — itself a shocker — during its July

meeting, which contradicted the premature press release.

At its July 8, 2015 meeting SFERS Commissioners were informed that the single investment package then being considered was worth just $26.1 million, not $125 million. SFERS Investment staff presented a skimpy two-page analysis after having taken over nine months to complete and present its due diligence analysis of the proposed investment. None of SFERS Commissioners asked why the Mayor was seeking $125 million for a package of loans only worth $26.1 million, or why he needs the extra hundred million.

This author performed a secondary analysis of 157 of the DALP loans already paid back, and 391 of the DALP loans then outstanding as of July 5, 2015, which secondary analysis revealed a whole host of problems and questions regarding the DALP loan pool. Among the disturbing findings was the fact that fully 12 — 7.6% — of the 157 loans already repaid returned no share of appreciation to the City, and only the principal amount of the loan was repaid, resulting in zero return-on-investment to MOHCD.

The skimpy two-page

analysis presented by SFERS staff to SFERS’ Commissioners

on July 8 claimed that the small 310-loan “package”

of $26.1 million in DALP loans has an Internal Rate of Return

(IRR) of just 5.2%, which doesn’t meet SFERS’ current

minimum investment guidelines rate of return of 7.5%.

The skimpy two-page

analysis presented by SFERS staff to SFERS’ Commissioners

on July 8 claimed that the small 310-loan “package”

of $26.1 million in DALP loans has an Internal Rate of Return

(IRR) of just 5.2%, which doesn’t meet SFERS’ current

minimum investment guidelines rate of return of 7.5%.

Commendably, SFERS Commissioner Brian Stansbury — an elected member of the Board and a Sergeant in San Francisco’s Police Department — peppered SFERS Investment staff with relevant questions regarding whether SFERS’ staff have experience with “Asset-Backed Liabilities Securitization,” “Collateralized Loan Obligation,” and assigning credit ratings to individual securities, noting they go hand-in-hand with the potential MOHCD DALP investment.

SFERS’ Chief Investment Officer Bill Coaker responded that no SFERS staff has such experience in any of these areas, and SFERS contracts with external managers for this expertise. There was no discussion of whether SFERS will have an “external” manager review the DALP loans, which amount to asset-backed liabilities and collateralized loans.

Stansbury and other Commissioners noted that no liquid secondary market exists for these loans, raising the question of why SFERS’ Board would make a highly illiquid investment in a pool of DALP loans that apparently no other secondary market will purchase.

Stansbury astutely

noted it would be unprecedented in

SFERS’ history to engage in a relationship with the City

under the guise of it being a financial investment

to further the City’s social policy goals.

Stansbury astutely

noted it would be unprecedented in

SFERS’ history to engage in a relationship with the City

under the guise of it being a financial investment

to further the City’s social policy goals.

Investing in MOHCD would set a really bad precedent for SFERS, as it may well sanction a form of “self-dealing” of one City department directly investing in funding another City department. What’s next? Investing in the PUC or MUNI?

San Francisco already has way too much of a slippery slope of corruption at City Hall, and SFERS’ Board should reject investing in MOHCD’s DALP loan pool for this reason alone.

Finally, SFERS would not be investing in “prospective” [future new] loans, it would be purchasing existing loans. The Mayor claims such an investment might “recapitalize” the DALP program. But that’s not what pensioners want done with their retirement funds.

And besides, the HTF is already on target to be “recapitalized” over a 30-year period with $1.3 billion in General Fund contributions, plus interest earned. As it is, Prop. “C” passed by voters in 2012 creating the HTF included a built-in recapitalization provision of funding an additional $2.8 million annually to the previous year’s General Fund allocation to the HTF.

Starting with its

first $20 million allocation in Fiscal Year 2013–2014 that

rose to $22.8 million in FY 2013–2014, the HTF and its DALP

program will reach an annual recapitalization appropriation of

$31.2 million by FY 2016–2017. Within just 12 short years

into its 30-year life, the HTF will reach an annual recapitalization

appropriation from the General Fund of $50.8 million by FY 2024–2025.

Starting with its

first $20 million allocation in Fiscal Year 2013–2014 that

rose to $22.8 million in FY 2013–2014, the HTF and its DALP

program will reach an annual recapitalization appropriation of

$31.2 million by FY 2016–2017. Within just 12 short years

into its 30-year life, the HTF will reach an annual recapitalization

appropriation from the General Fund of $50.8 million by FY 2024–2025.

There is no need to recapitalize the HTF using an “investment” from the retiree’s pension fund. Mayor Lee — along with Supervisor Cohen’s help — is simply making a political money grab here trying to tap into the pensioner’s pension system.

The Bond Is Too Vague: Vote “No”!

The Civil Grand Jury’s concerns about the raiding of the HTF to rescue the Housing Authority was a red-flag warning. It appears the HTF and AHF funds may be being used as slush funds to rebuild public housing and low-income housing, at the expense of building new affordable housing for moderate and medium-income housing.

Given the background documents describing potential planned uses of this bond, and the clear data in the Housing Balance Report from the Planning Department, that’s exactly what may well happen with this $310 million bond.

Handing MOHCD another $310 million for vague uses when it has sole discretion over the planned uses and ultimate spending decisions is simply wrong. That’s why we need a change to the City Charter to create a Commission or Board to provide oversight over all of MOHCD, and not just the current smaller commission that has oversight of only the successor agency to the Redevelopment Authority.

Luckily, former State

Senator and retired Judge Quentin Kopp and the San Francisco Taxpayers

Association are opposing the Prop. “A” bond. Kopp

notes that the bond measure is “… a virtual hodgepodge

of taxpayer money seeking to save City Hall big shots on our dime

from the results of their own failed housing policies.”

Luckily, former State

Senator and retired Judge Quentin Kopp and the San Francisco Taxpayers

Association are opposing the Prop. “A” bond. Kopp

notes that the bond measure is “… a virtual hodgepodge

of taxpayer money seeking to save City Hall big shots on our dime

from the results of their own failed housing policies.”

When you vote on Prop. “A,” make it a referendum on the housing policies of the Mayor and his out-of-control MOHCD: Vote “No!”

Then, urge your District Supervisors to place a City Charter change on the November 2016 ballot to create a Commission to oversee MOHCD, since the current Citizens General Obligation Bond Oversight Committee has a terrible track record of adequately providing oversight of various general obligation bonds, ranging from parks bonds to bond measures to rebuild our two public hospitals, the wastewater system improvement (WSIP) bonds, and our branch [public] libraries improvement bonds (BLIP), among other poorly-performing bond measures.

And while you’re at it, vote “Yes” on Prop.

“I,” Suspension of Market-Rate Development in the

Mission District. After all, we may need a similar citywide

moratorium on market-rate housing development until Supervisor

Jane Kim and other City leaders can hold hearings on the Housing

Balance Report and find effective solutions for providing a real

balance of affordable housing in San Francisco.

Monette-Shaw is an open-government

accountability advocate, a patient advocate, and a member of California’s

First Amendment Coalition. He received the Society of Professional

Journalists-Northern California Chapter’s James Madison Freedom of Information Award in the Advocacy category in March 2012. Feedback: monette-shaw@westsideobserver.

Postscript

Additional information came to light after this story was submitted for publication.

August 30 San Francisco Op-Ed

A second op-ed appeared in the Examiner’s

August 30 edition written by Peter Cohen and Fernando Marti, the

co-directors of San Francisco’s Council of Community Housing

Organizations.

A second op-ed appeared in the Examiner’s

August 30 edition written by Peter Cohen and Fernando Marti, the

co-directors of San Francisco’s Council of Community Housing

Organizations.

First, the pair of men assert the $310 million bond measure is the lynchpin of the City’s funding puzzle. This is nonsense, since there’s already over $2 billion in funding flowing to the Mayor’s Office of Housing via the HTF and AHF, among other sources, with more expected to follow.

Second, they assert a quarter of the bond ( $75 million) will be used for rehabilitation of our housing stock, another quarter will go to first-time homebuyer programs, and the remaining half ($150 million) will fund development of new permanently affordable homes. Data repeatedly presented in the City’s own records suggests that’s completely untrue.

As the table below shows, although the middle-income housing portion is 25.8% of the bond, there are four categories of programs in that category, including DALP Loan Expansion, the Teacher Next Door loans, Middle-Income Rental Program, and Expiring Regulations Preservation. Of the $57 million proposed on June 10, the two loan programs totaled just $15 million. Just $17 million was proposed for the rental program, and $25 million was proposed for preserving the expiring regulations rental units, for a total of $42 million.

Cohen and Matri are

wrong (unless these numbers have changed again since July 8).

One quarter of the bond is not going to first time homeowner loans.

Of the $57 million identified for middle-income housing, only

$15 million is for the two loan programs, representing just 5%

of the then-$300 million bond. The combined $42 million for the

two rental programs represents just 14% of the then-$300 million

bond. And large chunks of the middle-incoming portion of the bond

— whether at $57 million or the increase to $80 million —

may not be spent on new affordable housing at all as Marti and

Cohen hope, but may go instead toward preserving existing rental

housing.

Cohen and Matri are

wrong (unless these numbers have changed again since July 8).

One quarter of the bond is not going to first time homeowner loans.

Of the $57 million identified for middle-income housing, only

$15 million is for the two loan programs, representing just 5%

of the then-$300 million bond. The combined $42 million for the

two rental programs represents just 14% of the then-$300 million

bond. And large chunks of the middle-incoming portion of the bond

— whether at $57 million or the increase to $80 million —

may not be spent on new affordable housing at all as Marti and

Cohen hope, but may go instead toward preserving existing rental

housing.

Both men completely ignore that MOHCD will have sole discretion over how the bond will eventually be spent.

More Information, Less Clarity From Chief Economist

After this article was submitted for publication, San Francisco Chief Economist Ted Egan finally responded to a records request seeking the amounts of, and types of, developer incentives involved with the $310 million Affordable Housing Bond measure. He sent along another PowerPoint presentation but the document shows neither the amount of developer incentives that will be offered, nor the types of incentives.

The document does

state, however, that San Francisco should examine how to use tax

increment financing (TIF). TIF’s are a public financing method

used as a subsidy for redevelopment and infrastructure projects.

The TIF method of financing has been discontinued in the state

it began in, California, when Governor Brown abolished Redevelopment

Agencies in our state. But San Francisco is considering plowing

ahead with them, anyway. Great; more financing gimmicks for redevelopment

projects!

The document does

state, however, that San Francisco should examine how to use tax

increment financing (TIF). TIF’s are a public financing method

used as a subsidy for redevelopment and infrastructure projects.

The TIF method of financing has been discontinued in the state

it began in, California, when Governor Brown abolished Redevelopment

Agencies in our state. But San Francisco is considering plowing

ahead with them, anyway. Great; more financing gimmicks for redevelopment

projects!

TIF districts have attracted much criticism. One criticism of TIF projects is that as investment in an area increases, it is not uncommon for real estate values to rise and even more gentrification to occur. Won’t even more gentrification from rising and hot market-rate housing values just make affordable housing worse in the Mission District and the City?

The TIF process arguably leads to favoritism for politically-connected developers, implementing attorneys, economic development officials, and others involved in the processes. Just what we need: More political-favor cronyism for the politically-connected in San Francisco!

Capturing the full tax increment and directing it to repay the development bonds ignores the fact that incremental increase in property values likely requires increasing provision of public services, like schools and public safety staff.

Another slide in the presentation suggests creating a “Housing Affordability Fund,” but we already have the 2012 voter-authorized “Housing Trust Fund” (HTF) and a separate “Affordable Housing Fund” (AHF) within the City’s budget. Why do we now need a third fund?

The document suggests

making a new fund an “off-balance-sheet fund,” in order

to take debt off the City’s books, perhaps to conceal San

Francisco’s overall debt load. The goal of off-balance sheet

financing is to reduce or maintain a city’s debt at or below

a prescribed level so that its debt-to-equity ratio is low. Cities

having a favorable ratio obtain better credit ratings, among other

benefits.

The document suggests

making a new fund an “off-balance-sheet fund,” in order

to take debt off the City’s books, perhaps to conceal San

Francisco’s overall debt load. The goal of off-balance sheet

financing is to reduce or maintain a city’s debt at or below

a prescribed level so that its debt-to-equity ratio is low. Cities

having a favorable ratio obtain better credit ratings, among other

benefits.

Voters should reject off-balance-sheet funding for housing in San Francisco, until the City Charter is changed to create a Board or Commission to oversee all of MOHCD. There should be no off-balance-sheet funding.

Yet another slide in the presentation suggests creating more public-private partnerships involved in the DALP loan pool that is funded heavily from the overall HTF. Do we really want private developers gaining access to funds in the HTF? And do we want to pursue partnerships with “socially-motivated investors”? What level of transparency and accountability will be provided, and how much access to public records will extend to any private partnerships?

Another slide proposes

that the City purchase rent-controlled properties and convert

them to “deed-restricted units.” This sounds fine, except

when the deeds may change, we might find ourselves with the very

same problem with the “expiring regulations preservation”

where the affordable housing jumps back to market rate units.

How will “deed restricted units” be any different? Once

deeds face changes, won’t we have the same situation as with

the expiring covenants situation?

Another slide proposes

that the City purchase rent-controlled properties and convert

them to “deed-restricted units.” This sounds fine, except

when the deeds may change, we might find ourselves with the very

same problem with the “expiring regulations preservation”

where the affordable housing jumps back to market rate units.

How will “deed restricted units” be any different? Once

deeds face changes, won’t we have the same situation as with

the expiring covenants situation?

When Time magazine interviewed Mayor Lee in January 2014, in addition to stupidly claiming the City assumed middle-class San Franciscans were moving out of The City, he also said “Our city did pretty good in investing in low-income housing and trying to do as much as we could for the homeless. That was where our sentiments were.” Lee has assumed during his five-year tenure that middle-class San Franciscans were moving out, and focused on the homeless instead. What else is this Mayor assuming, given his annual $295,847 paycheck?

If voters approve this bond measure, Lee may use it just to sweep the homeless off the streets before Super Bowl 50.